The negative impact of geopolitical crises on tourism flows: the EU tourism policy as a tool for promoting them

Aspasia Aligizaki

University of Piraeus, Department Of International and European Studies

Abstract

The main objective of this study is to analyze the European Union's action to promote tourism where geopolitical risks can limit tourism flows. In particular this study attempts to explore the impact of the geopolitical risks and uncertainty on tourism arrivals in Europe and especially in South-Eastern Mediterranean area using recent official data from World Tourism Organization and at the same time to highlight how the tourism policy of the European Union can promote tourism flows.

More specifically, this study will try to capture the new context of contemporary tourism activity developing within the emergence of geopolitical risks as tourism has become more and more conditioned by geopolitics and, also, will attempt to shed light on the tourism policy of EU and how its “tools” can promote tourism besides the geopolitical risks that undermine it.

Therefore, this study is an exploratory analysis meant to identify the impact of geopolitical risks on tourism activities and how the European tourism policy can limit these risks.

Keywords: tourism, EU tourism policy, geopolitics, geopolitical risks, South-Eastern Mediterranean

- Introduction

In this modern era, the tourism sector is a crucial component for the economic advancement of both developed and developing states due to its unprecedented contribution in increasing foreign reserves by tourist income and providing employment opportunities for their citizens[1]. The tourism industry has many advantages for a country, including increased employment opportunities, tax revenues, income earnings and foreign exchange reserves. Thus, it has become an important sector for economic development worldwide. In the next 10 years, the tourism industry will increase the global GDP to 11.53% and it is anticipated that it will create 421 million jobs.[2]

However, it is obvious that the tourism flows and therefore the tourism earnings of every nation are negatively influenced by some factors such as terrorism and political unrest since tourists are prone to visit secure and safe locations.

Actually, living in a "geopolitical world" and in a "geopolitical society"[3] is a contemporary reality as the geopolitical risks have increased in recent years. But what we mean by geopolitical risks; The authors define the geopolitical risks as the risks associated with terrorists' attacks, wars, and tension between the states, influencing the normal course of international relations. The term “geopolitics” covers a wide field of events with a wide variety of causes and consequences, from terrorist attacks to climate change, from Brexit to the Global Financial Crisis. [4] .

Despite the great appeal of Fukuyama's theory[5], of a new world order after the end of the Cold War, an order that would be founded on a global liberal revolution, the new world system is still plagued by significant geopolitical ruptures and crises. Today it is easy to select only a few from so many events in recent years, to illustrate the dominance of geopolitics and the increase in geopolitical crises especially in the Southeastern Mediterranean region: Conflicts in the Eastern Mediterranean have a long history as far as Greece and Turkey are for many years at odds regarding the delimitation of maritime zones. Today, the region is affected by many tensions between Greece / Cyprus and Turkey, governmental conflicts in Syria, Iraq, or Libya and also territorial and religious conflicts between Israeli–Palestine. Also, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine represents a watershed not only in security policy but also in energy policy as long as demand for energy to replace supplies from Russia has increased. Already during the preparation for war, the new situation became noticeable in the rise of gas and oil prices that affected not only private households but also industrial enterprises and cause uncertainty for all Europe countries, included those in the region of Mediterranean.

The war in Ukraine has given new momentum to various transformations and crises that were already underway, which then began colliding with each other, increasing the sense of global disorder and acceleration, of geopolitical uncertainty, and of social upheaval. These changes caused by the geopolitical crises and mainly the war is illustrated with the following figure:

Figure 1. Ten issues that will shape international agenda[6]

As shown in the figure above, all these geopolitical and war-accelerated changes overlap and intertwine and cause uncertainty to many people who may feel insecure due to the rising prices of basic products and the inability to have access to common goods like food, energy and healthy environment and climate. Vulnerability and fragility are translated to uncertainty as it is also translated from collective security to individual survival.

And these are only a few, but there is a common feature: while the event is local or regional, the impact is global. As a result, the geopolitical risk has started being recognized as a global risk, with significant effects in several economic areas (finance, trade, business, tourism etc.) and particularly in the area of tourism [7]. The uncertainty that is provoked by geopolitical changes and risks can have a serious impact on tourism. A study conducted by Dragouni et al. (2016) was the first to show the effect of the economic policy uncertainty on tourism flows, and more specifically showed that sentiment and mood have a time- and event-dependent effect on tourism demand. The study discovered a significant effect on tourism when there is high uncertainty, whereas there is no spillover when there is low uncertainty.[8]

- The impact of geopolitical events on the tourism activity

If geopolitics is the expression of the act of power, tourism is the expression of freedom, which tends to be increasingly conditioned by these power games[9]. To what extent do geopolitical events affect the tourism activity? Globally, the number of international tourists has grown each year, despite the rise in geopolitical risks. However, there are several examples from the past that show that geopolitical crises can have a negative impact on tourism.

For example, after the repeated attacks in the French capital, Paris lost in 2016, 5% of its tourists and after the terrorist phenomenon in 2018 the security conditions were quite uncomfortable for tourists as additional security filters were put in shops, tourist objectives, on the streets, in railway stations, not to mention the usual ones in railway stations and were associated with delays, etc. Similar situations were in London, Brussels, Barcelona, and other cities. The secessionist effects in Catalonia 2017, Lugansk and Donbass 2014-2018 had the same impact on tourism, as from 25 million tourists in 2008, Ukraine accounted only 12 million in 2015 and similar examples are many.

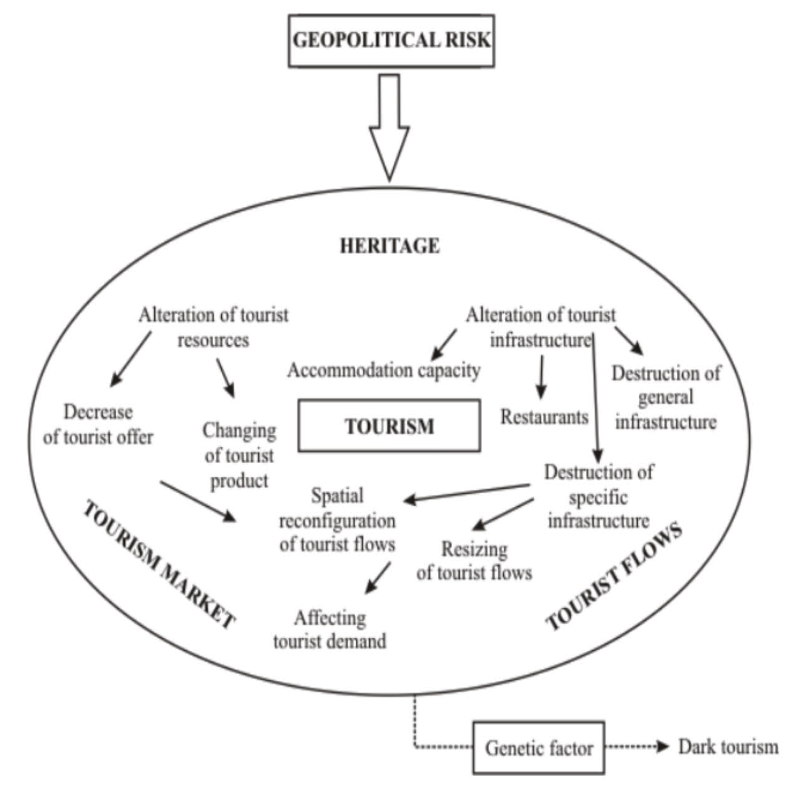

When war or when terrorist attacks are concerned, the tourist phenomenon is affected, in the most unpredictable ways, from the disappearance of landmarks, wiped off the face of the earth (such as Palmira in Syria, on UNESCO World Heritage List, dynamited by ISIS in 2017) up to quantitative and also qualitative changes in tourism flows. The figure below shows how geopolitical risks can affect tourist flows.

Figure 2: The theoretical scheme of the impact of geopolitical risks on tourism[10]

Moreover, the manifestation of geopolitical risks can generate a specific type of tourism, such as dark tourism (also black tourism, morbid tourism, or grief tourism), which has been defined as tourism involving travel to places historically associated with death and tragedy. The main attraction to dark locations is their historical value rather than their associations with death and suffering. For Example, holocaust tourism contains aspects of both dark tourism and heritage tourism the tourist resources consisting,[11]

- Geopolitical risks in the South - Eastern Mediterranean region

The Mediterranean has been a crossroads of peoples, religions, cultures, trades, and ideas. This region has been defined by British historian David Abulafia[12] as a sea between lands, a region that goes beyond its coasts to include Europe (to the north), North Africa (to the South), Anatolia and the Levant as far as Mesopotamia (to the East); and beyond, through its straits, the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula (to the South-East); and the Black Sea (to the North-East). Due to its position, it has been always a place of confrontation and clash between civilizations, empires and states that have fought over its control. Although, in the last five centuries, its importance has been declining – first, in favor of the Atlantic and, today, of the Indo-Pacific – it remains a key area in the global context, where the interests and ambitions of all major international players intersect.

The war in Ukraine has especially heightened energy and military challenges. The increasing militarization of the Mediterranean, like the rise of tensions between certain countries, does not stem from the Ukraine war only, but in some cases transcends and precedes it. This is the case with the tensions between Greece and Cyprus on the one side and Turkey on the other, the unresolved Libyan crisis, the effects of conflicts in Syria on the neighboring countries. The Ukraine war has worsened the picture and triggered a more heated rivalry between an increasingly proactive Russia and USA (and NATO allies), which had already emerged since the start of the Syrian crisis, in the 2010s. Moreover, ten years of unresolved wars and crises have forced millions of refugees and displaced persons to abandon their homes to seek refuge in Europe or other countries. This should be added to the thousands of economic migrants who move across the Broader Mediterranean in search for a better life, a large proportion of whom cross into Europe every year.

All these different crises ladder up to a larger and more general geopolitical game that has its focus in the South-Eastern Mediterranean and involves global powers such as the United States and European Union, Russia, China, India, as well as emerging regional players. This game is particularly important for European countries, as it goes beyond individual internal crises or cyclically resurfacing tensions between countries and it had a significant impact on the internal political life and economy of the countries of South-Eastern Europe, and in particular on the tourism revenues in them as it causes instability and by extension insecurity to the would-be visitors to them.

In an increasingly multipolar and disorderly world, where the Great Powers contend for spaces of influence in the various regions of the globe, if the Indo-Pacific remains at the core of Chinese and US interests, the South-Eastern Mediterranean has grown in importance. The war in Ukraine, which has led to a clear political break-up between Russia and the West, and - above all - has had serious repercussions in the area as for example the energy issue, with producing countries in the area becoming increasingly more important and influential not only because of the war in Ukraine, but also because of growing demand for energy from developing countries and the need for many large European countries to diversify their supplies. The need for states to secure their own energy resources or become energy transit hubs creates a flammable and volatile environment in the region that causes uncertainty and insecurity for potential tourists. Also, the energy crisis as a result of the war in Ukraine brings about an increase in the prices of all services and particularly in the prices of services related to tourism. And although the south-eastern Mediterranean was less affected by the energy crisis as it had the possibility to procure energy resources from other routes, the prices of energy resources are also higher in this region than in the past. As a result, tourism services are also burdened and consequently are currently more expensive, a fact which is expected to have a negative impact on tourism flows.

Finally, the rise of strong regional players - as the Gulf countries- and revisionist and maximalist states - as Turkey - which intend to assert themselves in an increasingly multipolar world with their own autonomous profile through a pure realistic foreign policy is related to a more general instability in the area which, as mentioned above, can cause insecurity for anyone thinking of visiting it .[13]

- Recent Data on tourism flows in Europe and in the Mediterranean region in 2023

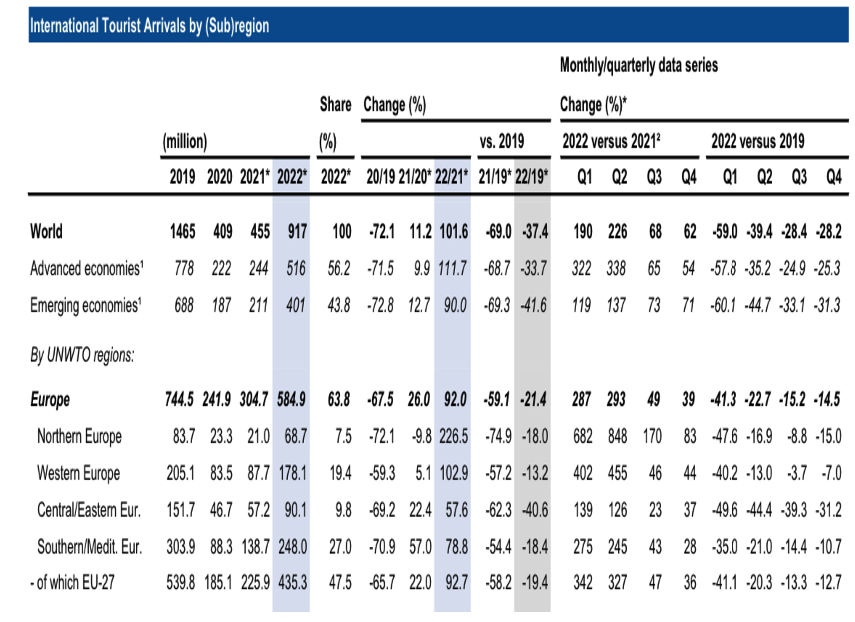

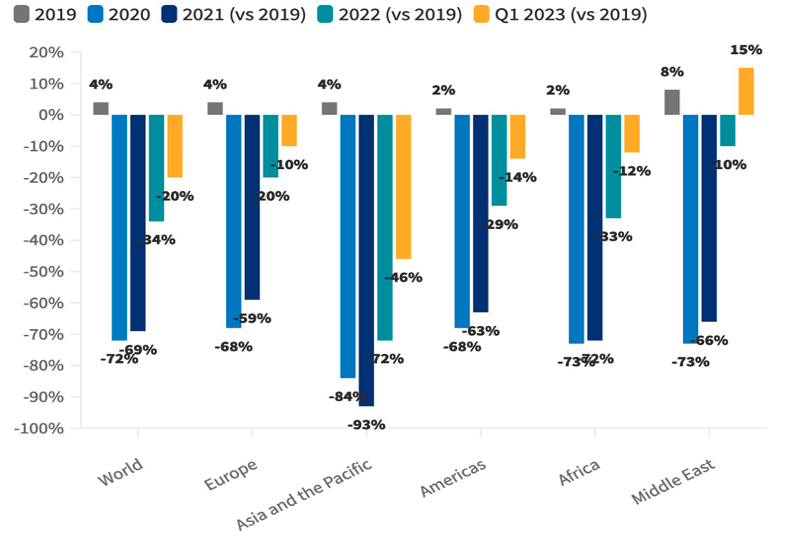

According to The UNWTO World Tourism Barometer - which is a publication of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) that monitors short term tourism trends on a regular basis to provide global tourism stakeholders with up-to-date analysis on international tourism - international arrivals reached 80% of pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter of 2023 (-20% compared to the same quarter of 2019) boosted by strong results in Europe and the Middle East, compared to a 66% recovery level for the year 2022 overall.

International tourism grew 86% in the first quarter of 2023 compared to the same period last year, reflecting continued strength at the start of the year. An estimated 235 million tourists travelled internationally in the first three months, more than double those in the same period of 2022. These results are in line with UNWTO’s forward looking scenarios for 2023 which projected international arrivals to recover 80% to 95% of prepandemic levels by the end of this year. The Middle East saw the strongest performance, with arrivals exceeding by 15% the number recorded in the first quarter of 2019. As a result, the Middle East is the first world region to recover pre-pandemic numbers in a full quarter.

Europe, the world’s largest destination region, reached 90% of pre-pandemic levels in Q1 2023, supported by robust intra-regional demand. Travel from the United States also contributed to results. According to data from the US National Travel and Tourism Office, US travel to Europe continued to show robust growth at the start of the year (+118% in January 2023 versus January 2022). Several destinations reported extraordinary growth in arrivals in the first quarter of (Q1)2023 versus Q1 2019, including Qatar (+98%), Saudi Arabia (+64%), Bulgaria, Serbia (both +27%), versus Cyprus (+10%).

According to the Panel of Experts, the challenging economic environment continues to be the main factor weighing on the effective recovery of international tourism in 2023, with high inflation and rising oil prices translating into higher transport and accommodations costs. Against this backdrop, tourists are expected to increasingly seek value for money and travel closer to home in response to elevated prices and the overall economic challenges. The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook (April 2023) indicates that global growth could fall from 3.4% in 2022 to 2.8% in 2023, amid financial sector turmoil, high inflation, and the impacts of three years of COVID. The uncertainty derived from the Russian aggression against Ukraine and other mounting geopolitical tensions also continue to represent downside risks.

Figure 3: International tourist activity by region. Source: World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (Data as collected by UNWTO, May 2023)[14] (Data as collected by UNWTO, May 2023)[15]

In the first quarter of 2023, international arrivals drew closer (80%) to the level they were at before the pandemic. More than 230 million tourists travelled internationally between the beginning of January and the end of March 2023, which is double the number in the same period of 2022. The Middle East saw the greatest recovery: arrivals were 15% higher than they were in 2019. UNTWO’s projections for the whole 2023 year foresee international arrivals recovering 80% to 95% of pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, as the figure above shows, Europe and in particular the under-analysis region of the south-eastern Mediterranean has shown an increase in tourist flows compared to the previous period of time.

- UNWTO’s Panel of Experts: geopolitical insecurity has a potential impact on tourism.

However, the UNWTO’s Panel of Experts warn that the economic situation in many countries could drag down. The economic situation remains the main factor weighing on the effective recovery of international tourism in 2023, with high inflation and rising oil prices translating into higher transport and accommodations costs. As a result, tourists may seek value for money and travel closer to their homes. Uncertainty derived from the Russian aggression against Ukraine and other mounting geopolitical tensions, also continue to represent risks and t causes an insecurity that can have a negative impact on tourist flows.

More specifically, UNWTO Secretary-General Zurab Pololikashvili said that while tourism is bouncing back nicely, new challenges have arisen in 2023 that may affect the volume of arrivals or the destinations that tourists choose. Although, the start of 2023 has shown again tourism’s unique ability to bounce back and in many places tourism flows are close to or even above pre-pandemic levels of arrivals, tourism can be affected by challenges ranging from geopolitical insecurity and the potential impact of the cost-of-living crisis on tourism. [16]

Therefore, geopolitical changes and tensions such as those described above create an insecurity for the potential visitors who, according to the experts on global tourism issues, may hesitate to visit areas such as the south-eastern Mediterranean if geopolitical risks are presented. High inflation, rising prices on energy and food products, disruptions of supply chains, and insecurity related to the military aggression of Ukraine impose heavy burdens on the provision and affordability of travel and hospitality services, limitations on travel have serious effects on the operations and prices of passenger transport across all Member States, including, but not limited to, flights and cruises.

The following chart shows trends over time across regions. While Asia-Pacific has seen the weakest recovery so far, the UNTWO believes this will accelerate though the year, especially given that China’s borders are now open.

Figure 4: The Middle East has seen the greatest recovery in tourism, followed by Europe. European tourism was boosted by intra-regional flows, and Southern Mediterranean Europe saw arrivals exceed those in 2019. Source: UNWTO[17]

- European union actions and initiatives in tourism

The European Union supports, coordinates, and complements the actions of EU countries related to tourism. EU tourism policy aims to maintain Europe’s position as a leading global destination and to turn Europe into a sustainable destination, bearing also its social and environmental aspects. Some objectives are, notably, to maximize the industry’s contribution to growth and jobs, as well as to promote cooperation between EU countries and develop the attractiveness of Europe as a destination.

EU recognizes the importance of promoting a sustainable, innovative and resilient tourism ecosystem and condemns Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified military aggression against Ukraine, and regrets its economic, political and humanitarian effects, including its negative impact on tourism, among other sectors, particularly in countries close to Ukraine.

Article 195 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [18] underlines that the Union shall complement the action of the Member States in the tourism sector, in particular by promoting the competitiveness of Union undertakings in that sector”. The EU, therefore, encourages the creation of a favorable environment and promotes cooperation between EU countries.

Over the past decade, Europe confirmed its position as the world-leading tourism destination. The European Commission proposed to co-create a transition pathway with industry, public authorities, social partners and other stakeholders. More specifically on December 2022, the Council of the European Union adopted the European agenda for tourism 2030. The agenda is based on the Commission’s transition pathway for tourism and includes a multi-annual work plan with actions to be taken by the EU countries, the Commission and tourism stakeholders.[19]. The report identifies 27 areas of measures for the green and digital transition and for improving the resilience of EU tourism.

It must be mentioned that the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) is an initiative launched jointly by the European Commission and the EIB Group (European Investment Bank and European Investment Fund) to help overcome the worst financial crisis since the late 1920s by mobilizing private financing for strategic investments. With EFSI support, the EIB Group is providing funding for economically viable projects, especially for projects with a higher risk profile than usually taken on by the Bank. It focuses on sectors of key importance for the European economy and may support tourism-related actions, such as, among other things: travel infrastructures (regional airports, ports, etc.), energy efficiency of hotels and tourism resorts, revitalization of brown fields for recreational purposes, tourism financing agreements, setting up “investment platforms” (IPs) dedicated to tourism.

EFSI is demand-driven and provides support for projects everywhere in the EU, including cross-border projects. Projects are considered based on their individual merits. There is the possibility to combined contributions from EFSI and ESIF (European Structural and Investment Funds).

Generally, EU invites Member States to exchange knowledge and best practices for developing and implementing tourism strategies at various governance levels, taking account of the economic, environmental, cultural and social sustainability of tourism and including the perspectives of visitors as well as local residents, organize awareness-raising activities on such themes as the benefits of the green and digital transformation, demand for sustainable offers, new skills needs and experimenting in tourism, and provide for the protection of local culture, including tangible and intangible cultural heritage, help to build resilience in the tourism ecosystem across sectors and different public and private actors.[20]

Despite the notable disparities between EU countries, tourism represents an important part of the EU’s overall economy. In 2019, it represented nearly 10% of the EU Gross Domestic Product and accounted for around 23 million jobs in the Union. The EU’s tourism sector is highly diverse and complex, covering globalized and interconnected value chains. It comprises businesses in several other subsectors, including food and beverage services, online information, and services providers (e.g., tourist offices or digital platforms), travel agents and tour operators, accommodation suppliers, destination managing organizations, attractions, and passenger transport (such as airlines and airports, trains, busses, and boats).

In conclusion since the tourism sector is very important for the European economy, perhaps gradually the European partners should proceed to jointly grant more powers to the European Union so that EU can take more measures at a supranational level to deal with the risks presented due to geopolitical crises, as they can threaten this so important for the economy sector. More Specifically, it might be useful if tourism were included in shared competences (Article 4 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union). The EU and its Member States will be then able to legislate and adopt legally binding acts and Member States will exercise their own competence only where the EU does not exercise, or has decided not to exercise, its own competence.

Conclusion

This study attempted to highlight the possible negative impact of the geopolitical crises and risks that are currently present in Europe and in the south-eastern Mediterranean. The geopolitical spillovers and subsequent instability create insecurity and discourage would-be travelers from visiting the regions in question while the energy and economic crisis, caused by the war in Ukraine, are likely to lead travelers to an option close to home to avoid the high cost of tourism services.

Therefore, the reduction of geopolitical risk can play a significant role in the tourism sector’s promotion. [21] Therefore, the government and officials must take necessary actions and required measures to ensure international harmony, national security, and public protection against such unpleasant events. By improving bilateral diplomatic relationships, safety, and security states can reduce the geopolitical risks and promote tourism flows. The geopolitical and energy crisis also provides an opportunity to reconsider the future of tourism and advance longstanding priorities such as addressing climate change and promoting a renewable energy transition [22].

The European Union and the Member States must encourage the structural changes required to transform the tourism industry in line with geopolitical challenges. Addressing these challenges also calls for international organizations, as the European Union, to use the full extent of their resources and financial instruments to restore travelers’ confidence, while helping the tourism industry to adapt and survive (Kara et al., 2020).[23]

The national tourist authorities throughout Europe and the European Union authorities, according to the official data of the World Tourism Organization, are right to be hopeful about the resurgence in tourism predicted for summer of 2023. However, it will be a mistake to turn a blind eye to the geopolitical challenges on the horizon.

The EU tourism experts and brightest minds in the national tourism sector must come together to strategize on the geopolitical and environmental issues that will affect us for the months and years ahead. Coordinated action in all areas is required to contribute to the further development of genuine, connecting tourism. But such action calls for member states to work even more sustainably, in a connected, high-quality, innovative way together with their European partners and the European Travel Commission. It may even gradually require that tourism be included among the “shared competences” so that the European Union can legislate and adopt legally binding acts when each member state cannot implement a tourism policy that will prevent the negative impact of geopolitical risks on tourism flows.

References

Abulafia, D., 2019. The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M., 2018. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. [pdf] Boston: Division of International Finance p. 6, Available at: https://www.bc.edu/matteo-iacoviello/%20gpr_files/GPR_PAPER.pdf%3E, [Accessed 20 June 2023].

Casini, E., 2023. The Mediterranean challenge, available at: https://www.med-or.org/en/news/la-sfida-mediterranea [Accessed on 20 June 2023] Available at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-05/UNWTO_Barom23_02_May_EXCERPT_final.pdf?VersionId=gGmuSXlwfM1yoemsRrBI9ZJf.Vmc9gYD [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

Colomina, C., 2023. The world in 2023: ten issues that will shape the international agenda, Available at: https://www.cidob.org/en/publications/publication_series/notes_internacionals/283/the_world_in_2023_ten_issues_that_will_shape_the_international_agenda [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, PART THREE - UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS, TITLE XXII – TOURISM, Article 195. OJ C 202, 7.6.2016, p. 135–13

Demir E., Gozgor G., Paramati S. R., 2020. To what extend economic uncertainty effects tourism investments? Evidence from OECD and non-OECD economies. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100758. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100758 [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

Dragouni M., Filis G., Gavriilidis K., Santamaria D., 2016. Sentiment, mood and outbound tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 80–96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.004, [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

European Agenda for Tourism 2030 - Council conclusions (adopted on 01/12/2022) Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15441-2022-INIT/en/pdf. [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

European Commision, Transition Pathway for Tourism, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/49498

Fukuyama, Francis, The End of History and The Last Man, The Free Press, New York, 1992, p.66

Ghalia, T., Fidrmuc, J., Samrgandi, N., Sohag, K., 2019. Institutional Quality, Political Risk and Tourism. Tourism Management, 32, pp. 1-15.

Helnarska, K. COVID-19, 2022. European Union Actions to Support Tourism, , European Research Studies Journal, Volume XXV, Issue 1, 646-656, https://ersj.eu/journal/2877 [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

Kara, A., et al. 2020. Once the dust settles, supporting emerging economies will be thechallenge, 11 May 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/05/11/once-the-dustsettles-supporting-emerging-economies-will-be-the-challenge/ [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

Munoz, J.M., 2013. Handbook on the Geopolitics of Business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, p.4

Neacsu, M. Negut, S. and Vlasceanu, G., 2018. The Impact of Geopolitical Risks on Tourism, The AMFITEATRU ECONOMIC journal, 20 (12)

Neguț, S. and Neacșu, M.C., 2013. Tourism, Expression of Freedom in The Global Era.International Journal for Responsible Tourism, 2(3), pp. 45-53.

Normand, F., 2009. Les États-Unis présentent le principal risque géopolitique. Les Affaires, Available at: https://www.lesaffaires.com/strategie-d-entreprise/entreprendre/lesetats-unis-presentent-le-principal-risque-geopolitique/500961 [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, 2023. Vol. 21, issue 1, available at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023- {Accessed on 20 June 2023],

World Travel & Tourism Council. (2019). Economic Impact, Malaysia 2012. Available at: http://www.wttc.org/ [Accessed on 20 June 2023]

[1] Demir E., Gozgor G., Paramati S. R., 2020. T

o what extend economic uncertainty effects tourism investments? Evidence from OECD and non-OECD economies. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100758. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100758 [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[2] World Travel & Tourism Council. (2019). Economic Impact, Malaysia 2012. Available at:

http://www.wttc.org/[Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[3] Munoz, J.M., 2013. Handbook on the Geopolitics of Business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

Publishing, p.4

[4] Caldara, D. and Iacoviello, M., 2018. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. [pdf] Boston: Division

of International Finance .p.6 , Available at: https://www.bc.edu/matteo-iacoviello/%20gpr_files/GPR_PAPER.pdf%3E, [Accessed 20 June, 2023].

[5] Fukuyama, Francis, The End of History and The Last Man, The Free Press, New York, 1992, p.66

[6] Colomina, C. (2023) The world in 2023: ten issues that will shape the international agenda, Available at: https://www.cidob.org/en/publications/publication_series/notes_internacionals/283/the_world_in_2023_ten_issues_that_will_shape_the_international_agenda [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[7] Normand, F., 2009. Les États-Unis présentent le principal risque géopolitique. Les Affaires,

[online] Available at: https://www.lesaffaires.com/strategie-d-entreprise/entreprendre/lesetats-unis-presentent-le-principal-risque-geopolitique/500961 [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[8] Dragouni M., Filis G., Gavriilidis K., Santamaria D. (2016). Sentiment, mood and outbound tourism demand. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 80–96.Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.06.004, [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[9] Neguț, S. and Neacșu, M.C., 2013. Tourism, Expression of Freedom in The Global Era.

International Journal for Responsible Tourism, 2(3), pp. 45-53.

[10] Neacsu, M. Negut, S. and Vlasceanu, G. 2018. The Impact of Geopolitical Risks on Tourism, The AMFITEATRU ECONOMIC journal, 20 (12) p.879

[11] Neacsu, M. Negut, S. and Vlasceanu, G. 2018. The Impact of Geopolitical Risks on Tourism, The AMFITEATRU ECONOMIC journal, 20 (12) pp. 870

[12] Abulafia, D (2019). The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019

[13] Casini, E. 2023. The Mediterranean challenge, available at: https://www.med-or.org/en/news/la-sfida-mediterranea [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[14] Available at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-05/UNWTO_Barom23_02_May_EXCERPT_final.pdf?VersionId=gGmuSXlwfM1yoemsRrBI9ZJf.Vmc9gYD,

UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, 2023. Vol. 21, issue 1, available at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023- {Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

01/UNWTO_Barom23_01_January_EXCERPT.pdf?VersionId=_2bbK5GIwk5KrBGJZt5iNPAGnrWoH8NB

[16] Available at: https://monitor.icef.com/2023/05/unwto-data-shows-that-international-tourism-arrivals-are-approaching-pre-pandemic-levels[Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[17] Available at: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-05/UNWTO_Barom23_02_May_EXCERPT_final.pdf?VersionId=gGmuSXlwfM1yoemsRrBI9ZJf.Vmc9gYD, [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[18]Consolidated version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, PART THREE - UNION POLICIES AND INTERNAL ACTIONS, TITLE XXII – TOURISM, Article 195. OJ C 202, 7.6.2016, p. 135–13

[19] European Commision, Transition Pathway for Tourism, available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/49498

[20] European Agenda for Tourism 2030 - Council conclusions (adopted on 01/12/2022) Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15441-2022-INIT/en/pdf. [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[21] Ghalia, T., Fidrmuc, J., Samrgandi, N., Sohag, K. 2019. Institutional Quality, Political Risk and

Tourism. Tourism Management, 32, pp. 1-15.

[22] Helnarska, K. COVID-19, 2022. European Union Actions to Support Tourism, , European Research Studies Journal, Volume XXV, Issue 1, 646-656, https://ersj.eu/journal/2877 [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]

[23] Kara, A., et al. 2020. Once the dust settles, supporting emerging economies will be the

challenge, 11 May 2020. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/covid19/2020/05/11/once-the-dustsettles-supporting-emerging-economies-will-be-the-challenge/ [Accessed on 20 June, 2023]