STRATEGIC TEAM ALIGNMENT: THE LUXURY HOTEL MANAGERS’ PERSPECTIVE DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Charalampos Giousmpasoglou1, Marina Brook2

Department of People & Organisations, Bournemouth University, Dorset House, Talbot Campus, Poole, BH12 5BB, UK, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.1,

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. 2

ABSTRACT

This study explores strategic team alignment during the COVID-19 pandemic, through the views and experiences of luxury hotel senior managers in the UK. The alignment of team members has always been crucial to the success of any organisation; however, during the COVID-19 pandemic the hospitality industry was one of the worst affected, experiencing large scale staff reductions, temporary or permanent. During this time the luxury hotel managers played a key role for staff motivation, support, and the maintenance of the hotel unit’s operational capacity.

The aim of the study was to identify how senior managers implemented alignment strategies and managed the COVID-19 pandemic, whilst keeping their team members engaged and motivated. A qualitative study was conducted in winter 2021, through in-depth semi-structured interviews via zoom, with 12 luxury hotel senior managers (GMs and department managers) from London and Berkshire. Access was secured by the author’s personal network and by using the snowballing technique. All the interviews were voice recorded and professionally transcribed; content analysis was employed for the collected data.

Three key themes emerged from data analysis namely: the strategic alignment creation process; transparency and engagement to manage the pandemic impact on team members; and managing change.

The practical implications of this study suggest that during crisis and unprecedented times, strategic alignment is essential to keeping teams engaged. During the crisis it is imperative that the senior managers demonstrate strong leadership and provide support to staff in individual and team level. In addition, the luxury hotel units’ senior managers are acting as change agents who help the organisation to survive during the crisis and ultimately lead to full recovery.

This study contributes to the existing research and theoretical frameworks on strategic team alignment during contingencies and crises. The findings of this study enhance our knowledge in this emerging and under researched field, through the views of the key actors (luxury hotel managers).

The study limitations include a small sample in a single region/country from the senior managers’ perspective. Future studies should include other key stakeholders (i.e. staff and customers) in different countries / cultural contexts.

Keywords: Strategic team alignment, Luxury Hospitality, Senior Managers, COVID-19

1. INTRODUCTION

The Coronavirus disease, also known as the COVID-19 pandemic, has resulted in severe consequences caused by its rapid spread worldwide, with the hospitality industry being one of the hardest-hit (UNWTO, 2020). The world had to react to the unprecedented global health, social and economic emergency with an urgent need to contain the virus. As an immediate result of the pandemic impact, the world experienced strict quarantines, travel restrictions and meticulous hygiene protocols. The hospitality industry was hit hard, with a dramatic drop in occupancy and average room rates, not only due to the new rules but also due to a considerable reduction in guests’ confidence (Le & Phi, 2020). In practical terms, the hospitality industry suddenly did not have guests occupying the hotel rooms. Business survival became the key focus for both independent operators and chains; in addition, hoteliers also focused on getting prepared for the guests' return, as well as taking care of their staff health and wellbeing (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021). This oppressive situation has created anxiety amongst team members, mainly due to the threat of redundancies and general insecurity regarding their employment future (Wong et al., 2021). During times of uncertainty, it is imperative to ensure that teams remain aligned and focused to the achievement of their strategic goals.

The strategic alignment of team members within an organisation, influenced by strategic leadership, is crucial to success (Khadem, 2008). It can be suggested that strategic alignment cannot be achieved in teams where team members are unmotivated, uninterested, and unhappy. Leaders must therefore motivate and inspire their team members in order to achieve complete alignment. It is also argued that the external business environment will remain unpredictable and volatile for the foreseeable future; it is therefore vital to have teams in place, who all understand the goal and can react quickly and efficiently to the ongoing situation (Mayo, 2020). During the pandemic, the employees’ personal and professional lives have been affected severely; as a result, team members’ cohesion and alignment has been a fundamental function for hospitality leaders. Aligning team members towards one goal allows focus and the aim to collectively achieve this goal (Middleton & Harper, 2007). The goal in this case was successful business recovery and return to pre-COVID19 occupancy levels.

This study aims to gain deep and meaningful insights through the experiences and recommendations of senior managers within the luxury hotel industry who have actively led and steered their team members through the COVID19 crisis. There is limited research on team members' strategic alignment in luxury hotels during a crisis, especially during the current situation, due to the industry never experiencing anything like it before. Additionally, only a few studies have focused on hospitality leaders as change agents and investigated how to manage contingencies and crises (Blyney & Blotnicky, 2010; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021; Marinakou, 2014). Hospitality leaders are also the key individuals who monitor, control and coordinate crisis management plans within hotel units; for this reason, they are considered as valuable strategic assets for any hotel (Giousmpasoglou, 2019). In addition, there is limited research regarding the employment of strategic teams’ alignment as a tool for business recovery after crisis. It is expected that the findings presented in this study will contribute on the existing literature, and also provide meaningful managerial recommendations for practitioners.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Strategic alignment

Strategic alignment is a critical function in organisational and departmental level; it can be defined as “the degrees to which each employee's interests and actions support the organisation's key goals” (Robinson & Stern, 1997, p.104). Khadem (2008) states that alignment is crucial to an organisation’s success, adding to Labovitz (2004) original statement that aligned organisations will remain more competitive than those who are not. Khadem (2008) suggests that an effective business strategy will encompass team member alignment, so everyone within the organisation will know and understand the strategy/goal and seek to contribute to it. On the other hand, when multiple individuals move in the same direction but without partnership or towards the same goal, they are misaligned. Kaplan & Norton (2006) state that the correct alignment usage will create positive benefits for an organisation, together they produced a perspective framework on how an organisations unit should be balanced. This describes how the unit will produce shareholder value through enhanced guest relationships driven by superiority in internal practices. These practices will then be improved by aligning people, culture, and strategy.

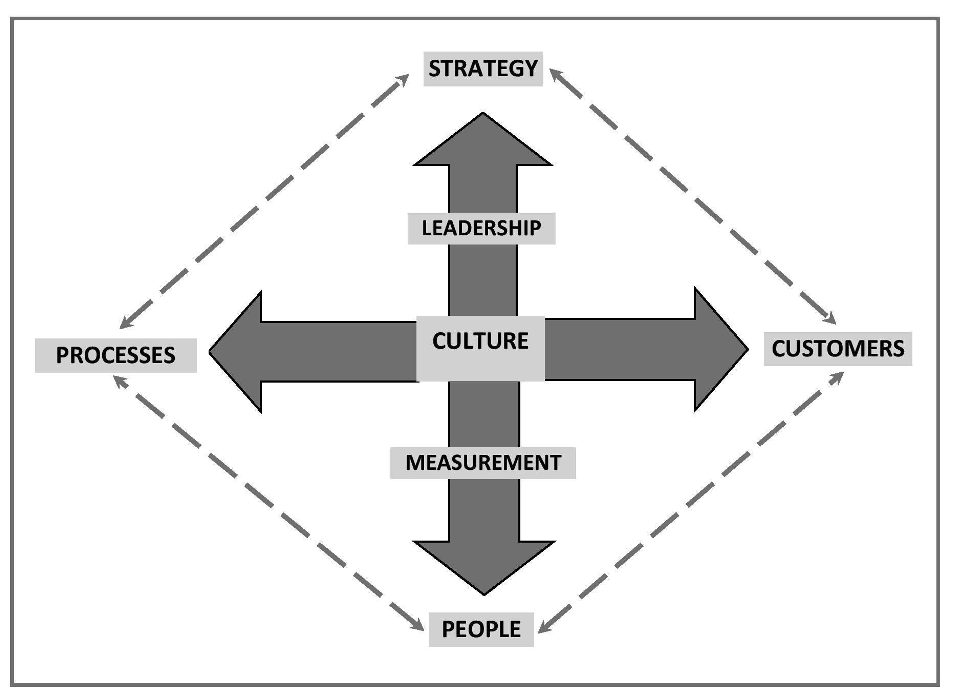

Figure 1: Labovitz and Rosansky’s alignment model

Source: adapted from Labovitz & Rosansky (1997), p.44

Culture plays an important role in creating team member alignment, when implementing their strategy, values and vision (Serfontein, 2009). In this case organisational culture functions in different levels: it presents a frame of reference for new and existing strategies, adopts uniform communication patterns, creates networks, and informs strategic decisions. There is the assumption that certain types of organisational culture can lead to increased organisational performance, however, this is reliant on the culture being shared and communicated throughout the entire organisation (Serfontein, 2009). Bipath (2007) states that an organisation with a strong culture will exceed those with uncertain cultures, if an organisation does not implement the correct cultural development, then it will be unable to produce positive performance and a sustainable competitive advantage. Therefore, senior managers, leaders and change agents should drive a culture transformation and create team member alignment throughout the organisation.

2.2. Strategic alignment in hospitality context

Strategic alignment is vital to any hospitality organisation's performance as it allows the business to respond effectively to the external environment. It has been noted that organisations can still work when they are misaligned (Pongatichat & Johnston, 2008); there are often conflicts between employees’ personal goals and the organisations. However, an aligned organisation will ultimately create a more efficient organisation that can react quickly to external environment changes (Khadem, 2008). Kaplan & Norton (2006) state that it produces dramatic benefits for organisations and is therefore critical for organisations to achieve alignment throughout their business. If the organisation is aligned, it has the potential to innovate and reach higher and sustainable performance levels. An aligned hospitality organisation will benefit from greater employee and customer satisfaction producing greater returns. Greater employee satisfaction is especially important within the hospitality industry due to it being purely customer-service driven, therefore the organisations team members are their sole ambassadors, emphasising the importance of engaged and motivated employees to be successful (Chi & Gursoy, 2009).

Through alignment, hospitality organisations can improve their effectiveness, especially in people management. Labovitz (2004) suggest that hospitality managers at all levels, can utilise strategic alignment practices to grow excellent people, continually advance business practices, and become guest focused. Further research indicates that, many authors support the idea that the organisation's alignment is an essential part of an organisation's success and survival (i.e. Fonville & Carr 2001; Khadem, 2008; Kim & Mauborgne 2009). The strategic alignment of hospitality organisations during the COVID-19 pandemic was crucial their survival: without maintaining total alignment of employees, organisations would experience challenges once lockdown regulations have lifted. The decline in the hospitality industries financial situation has created uncertainty regarding job security, forcing employees to either accept redundancy, early retirement or go on a government furlough scheme where that was available (Evans, 2021). Due to these unprecedented circumstances, employees demonstrated high levels of anxiety and stress, affecting significantly their performance at work (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021). This has emphasised the need for management within hospitality organisations to keep their team members engaged and aligned to manage the rise in occupational stressors (Darvishmotevali & Ali, 2020).

2.3. Crisis management

Crisis management is a critical function to an organisation’s survival. More specifically, an organisation's knowledge and preparedness, play a key role in the prevention and successful crisis management and recovery if one should occur. Paraskevas & Quek (2019) defined a crisis as a significant event that can result in adverse effects that threaten the survival of organisations. The current COVID-19 pandemic has been classed as a crisis and resulted in the hospitality industry being sent into an unprecedented recession (WHO, 2020). Other major crisis’ that impacted the global hospitality industry in the past 20 years (i.e. natural disasters, terrorist attacks and epidemics like SARS and H1N1) were used as benchmarks in this crisis management planning. Kim et al. (2005) found that during the SARS crisis it was essential to establish efficient internal and external communication channels, to reduce the negative impacts of the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused a revenue loss to the hospitality sector greater than ever experienced before (Rodrigues & Kumar, 2020). This includes the loss due to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the SARS epidemic and the 2008 recession. The implementation of effective crisis management plans and practices were required for any hospitality business survival in global scale (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2021).

The existing literature on crisis management within the hospitality industry is limited and does not consider that a crisis can vary in impact, scale, and duration (Speakman & Sharpley, 2012). The models tested are more tourism-focused than hospitality and do not provide practical strategies to support hospitality organisations during specific situations like the global pandemic (Ritchie & Jiang, 2019). In addition, the current research is based on the preparedness of crisis management practices, focusing on the tourism industry (Hillard et al., 2011; Novelli et al., 2018), with limited studies on the hospitality industry. Therefore, the hospitality industry is now seeking key strategies for how to cope in response to COVID-19, showing an urgent need to fill a research gap. With the pandemic being spread worldwide and the severity in each country varying at different times, the recovery has been much longer than expected, crisis management strategies being continuously adapted, with past research on crisis management practices focusing on a specific time frame and the organisation as a whole, rather than the people within it (Israeli et al., 2011).

It is argued however, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 a number of studies investigated crisis management in hospitality context from different perspectives. Baum et al. (2020) question whether the situations faced by hospitality workers as a result of the pandemic, are seed-change different from the precarious lives they normally lead, or just an amplification of the “normal”. Giousmpasoglou et al. (2021) investigate the role of luxury hotel general managers (GMs) during the pandemic in 45 countries. The GMs’ role as change agents, is viewed as the stepstone to business recovery in hotel units. Jones and Comfort (2020) provide a reflective review of changes in the relationships between sustainability and the hospitality industry following the onset of COVID-19. Breier et al. (2021) suggest that the business model innovation (BMI) might be a solution to recover from and successfully cope with the COVID-19 crisis. Filimonau et al. (2020) found that the levels of organisational resilience and the extent of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices reinforce perceived job security of managers which, in turn, determines their organisational commitment. The above, are just a few examples of the recent interest on crisis management related studies, conducted in hospitality context. This study focuses on strategic team alignment in luxury hotels during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following section discusses the methodology approach, research tools and data analysis employed for this study.

3. METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was followed on this study. This approach produces data on thoughts and experiences i.e. using interviews and focus groups (Flick, 2018; Campbell, 2014). The research area is based on personal opinions making it subjective, meaning qualitative research is required over quantitative to produce rich and in-depth results. Qualitative research allows description, interpretation, and in-depth insight into the specific concepts being researched (Carlsen & Glenton, 2011); it also allows the exploration of emerging and common themes and trends (Saunders et al., 2009). These qualitative views and recommendations produced first-hand rich information on strategic employee alignment within luxury hotels during a crisis.

3.1. Research tools and sampling

Semi-structured interviews have been selected as the data collection method due to their ability to obtain detailed thoughts and feelings on an individual level (Qu & Dumay, 2011). The use of semi-structured interviews allowed some form of structure and the guarantee that all participants were asked the same questions, however if the researcher had any questions, the semi-structured approach allowed probing to query any points made (Altinay et al., 2015). The interview questions were formulated based on the existing literature, and the themes and gaps that emerged in the literature review. The interview questions focused on the managers’ views and suggestions for successful team member alignment during a crisis; a secondary area of enquiry was the managers’ recommendations for university graduates and young leaders.

The interviews were conducted online with selected luxury hotel managers employed in 5* hotels in London and Berkshire. The respondents were selected through non-probability sampling, based on the researcher’s existing network (Vehovar et al., 2016). Participants were approached via LinkedIn and email, with a tailored message that included a summary of this study, and the interview questions. In addition, a consent form and information regarding the study’s compliance with Bournemouth University research ethics standards, was provided to all participants. In total, 12 out of 15 candidates that were contacted agreed to take part in this study; the managers were chosen based on their position within the chosen luxury hotels and their willingness to participate and share knowledge. The senior managers who took part, work for luxury hotel companies, operating in a global environment with multiple hotels worldwide. They converse with international customers, global acquisition and hugely diversified workforces, all essential parts of their operations. The purpose of the interviews was to obtain insight into how luxury hospitality managers align their team members towards success during the pandemic.

3.2. Data Analysis

A thematic analysis was employed to analyse the collected data from the interviews. Thematic analysis is a method of identifying, describing and reporting themes found in a data set (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Originally branded as a poor research analysis tool, it has now been argued by multiple researchers to produce trustworthy and insightful findings (King, 2004; Thorne, 2000). Emerging themes were noted and analysed throughout the interviews conducted in this study, by using colour coding and thematic analysis.

The data collected from the interviews were anonymised and then, the researcher transcribed the 12 interviews. Based on the notes taken, the literature and the objectives of this study, sub-themes were created. When analysing the data produced from the study, two types of analysis were used: thematic and comparative. Comparative analysis allows data collected through respondents and themes to be compared (Harding and Whitehead, 2020). Through thematic analysis, the common themes were identified, and through comparative analysis, the themes that emerged from the different luxury hospitality managers were compared. The themes were reviewed based on their relevance to the study, and three sub-themes emerged namely: strategic alignment creation; transparency and engagement with team members; and, managers encouraging pro-active change.

4. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Participants’ profile

The 12 participant managers have more than 10 years’ experience in luxury hospitality, with 41% having between 20-30 years’ experience and two of the twelve luxury managers having over 45 years of luxury experience. The low number of female participants (33%) included in the study attributed to the management within luxury hospitality still being very male dominated (Marinakou, 2014). The participant list was made up of an equal split of general managers, operations managers, and human resource managers. To simplify the process of coding for the anonymized data analysis, each manager was given a designation from LM1 to LM12. The manager profiles are shown below in Table 2.

Table 2: Participant managers’ profiles

|

Coding |

Job Title |

Gender |

Years of Service |

Hotel Location |

|

LM1 |

General Manager |

Female |

40-50 |

Berkshire |

|

LM2 |

General Manager |

Male |

20-30 |

London |

|

LM3 |

General Manager |

Male |

20- 30 |

London |

|

LM4 |

General Manager |

Male |

50+ |

London |

|

LM5 |

Operations Manager |

Male |

10-20 |

Berkshire |

|

LM6 |

Operations Manager |

Male |

20-30 |

Berkshire |

|

LM7 |

Operations Manager |

Male |

10-20 |

London |

|

LM8 |

Operations Manager |

Male |

10-20 |

Berkshire |

|

LM9 |

HR Manager |

Female |

20-30 |

Berkshire |

|

LM10 |

HR Manager |

Female |

10-20 |

London |

|

LM11 |

HR Manager |

Male |

20-30 |

London |

|

LM12 |

HR Manager |

Female |

10-20 |

London |

4.2. Theme 1: Strategic alignment creation

When discussing the strategic alignment of team members with the managers, two key trends emerged: culture and communication. LM9 suggests that “Culture is the heart of it all, it’s the glue that has kept us together through this and will continue to into the future”. All 12 managers stated that culture and communication are essential when aligning team members towards success within an organisation. LM 1-12 unanimously highlighted the significance of culture when aligning team members towards one goal. In this vein, they also emphasised the importance of having a good organisational culture and team members around you who are passionate about what they do “…willing to live and breathe your culture” (LM5). Khadem (2008) stated that culture and vision were vital for employees to be aligned and follow the goal set by the organisation. It has been argued that great service in hospitality is often rare due to its complicated nature, it requires the true alignment of team members which is driven through service tradition, culture and focused strategies (Schneider et al., 2003). Four of the managers stated that even though it was evident that a positive organisational culture leads to success, it is often where most organisations fail: “…I had to create a whole new culture as the hotel did not work as one, I changed everything in order for everyone to be aligned to one goal” (LM2). This supports the idea that implementing culture isn’t always as simple as it seems, when LM2 became GM in a luxury hotel in London, the culture in place was ineffective and employees were misaligned. It’s a challenge that many luxury hotels face, which ultimately causes conflict when aligning team members.

Communication was also a key element in the mangers journey during the COVID-19 pandemic: each of them referred to communication as being vital for any organisation to run, however the past year making it more important than ever. According to LM1 “you can have an amazing leader, but without communication throughout the rest of the organisation it won’t work”. If an organisation lacks communication, then any strategies or managerial processes implemented will not be successful (Jackson & Schuler, 1995); on the other hand, in an organisation with effective communication the team members within it are more likely to be strategically aligned acting in coordination to achieve the set goals (Jorfi et al., 2014).

4.3. Theme 2: Transparency and engagement

When the participants were asked how they managed the crisis amongst their team members, alongside communication and culture, “Transparency” and “Engagement” were the most frequently used words used, with all 12 managers saying these two areas were essential to manage the impacts of the current crisis on their teams. When there was a rapid increase in cases, and the Pandemic became apparent, most hospitality organisations were forced to implement the emergency phase. This usually includes reducing staff hours, redundancies, and unpaid leave (Kim et al., 2005). Transparency with team members played a vital role in keeping them engaged and informed about their organisations: “Keeping team members engaged and mentally stimulated is essential, the mental wellbeing issue is on the rise, and that's why I think it's so important to stay in touch. We need to use this time to motivate, inspire and coach our teams” (LM2).

Through frequent contact and transparency, the managers were able to ease team members anxieties and change team members attitudes and actions into more aligned actions, that in the long term will improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the business (Zaccaro & Kilmoski, 2002; Yukl, 2012). LM9 says: “We tried to put everyone at ease and make sure they felt comfortable, that was fundamental, once they felt safe, they were ready to hear the action plan and be a part of the road to recovery”.

LM 1,3, 6, 7, 8 and 10 noted that this time allowed creativity and innovation, the managers would set tasks in order to keep their team members engaged, however: “It was key that the tasks were relevant and substantial enough to keep their minds working…” (LM5). Many of the leaders found that through setting these tasks each week and the team members having the time to really think about them, they remained engaged and creative. A growing number of research studies focuses on what leaders can do to foster creativity and innovation within their teams (i.e. Hughes et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2019; Rosing et al., 2011). However, the research on this topic area is still rather broad and limited (Brem et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2018). Therefore, gaining insight into how these managers adapted and thought outside of the box during “the new normal” produces rich and valuable data. Zoom calls, quizzes, cooking classes and work-related tasks/presentations were amongst the most common activities set by the senior managers. LM5 commented that: “This approach worked so well that I will continue with it even when we go back to normal, I know we will have less time, however I will find the time as it has been such an important part of the past year, something the team have enjoyed and something I now feel is essential to keep us all creative, engaged and aligned”. In addition, according to Rosenbusch et al. (2011), encouraging team creativity and innovation is essential and very effective to sustain competitive advantage.

The team members in luxury hotels normally spend much time together, sometimes more that with their families; nevertheless, during the COVID-19 pandemic they found themselves being home alone at most of the times, with negative impact on their health and well-being. LM9 suggests that “it’s all about staying connected, making sure the whole team is nurtured… by doing that we create a family, that’s all aligned to one goal”. This ‘family’ theme that emerged throughout the interviews is typical of the luxury hotel sector (Bharwani & Jauhari, 2013; Giousmpasoglou, 2019). It was evident that the managers key priority in this difficult time was their team members’ wellbeing: “I am responsible for every single team member, they are part of our big family, it was so hard to see any of them struggle and not be able to comfort them face-to-face” (LM2). LM1, 3,4, 6, 10 and 11 also referred to their team members as being part of a family: “Without a happy and healthy team when we return, there will be no return, so they are my key priority at the moment, we will only overcome this situation if we are all in it together” (LM10).

4.4. Managers encouraging proactive change

During the COVID-19 pandemic, managers in luxury hotels had to step up and react quicker than usual. It was essential they demonstrated alignment whilst reacting to the huge change occurring within their luxury hotels: “I think every luxury hotel has big binders labelled crisis management, but I don’t think any binder could have prepared us for this situation… the right leaders within your hotel and a strategically aligned team pre-pandemic all striving for one goal, then you can conquer any situation” (LM2).

Only a small number of studies have focused on luxury hospitality leaders when tackling a crisis, the current literature is very sparse, but is likely to become a lot more common after the current situation (Speakman & Sharply, 2012). It is essential that hotel managers are pro-active and develop a defence mechanism for when a crisis should occur (Paraskevas & Altinay, 2013). This study aims to gain some insight into the biggest challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and how the luxury managers overcame them. LM5 opened-up and expressed his feelings regarding his challenging role: “I am the leader for my team, and I always will do the best I can for them, but the hardest thing was needing to appear strong at all times, when sometimes I was just as confused as they were”.

However, LM5 then went on to comment that through the communication of his own leaders, he realised that communication was so vital, and it was ok to feel this way, that everyone would have experienced it at some point. LM7 spoke about the importance of team members’ support: “They are not alone, everyone is struggling at this time and I think this is one of the biggest things I try to instil in my meetings…I felt the best way to do this was to let them in on what I was worried about and how I overcame it”. However, in the face of the uncertain situation, many of the managers seemed confident and determined to tackle the challenges of the pandemic to the best of their ability. They saw this situation as a chance to seize opportunity and make this difficult year worth something. LM2 convinced the owners that “it was the best time to invest and make a noise, we must take advantage of this terrible situation, be creative and forward thinking”. All the participants mentioned similar experiences, they saw it as a chance to be creative and get their team members involved in making the “new normal” within the hotel run efficiently: “I need my team to be behind the new practices…if they are not involved then they will not be passionate about what they are doing.” (LM7).

Ten out of twelve participants mentioned getting their teams involved with reopening plans to keep them stimulated and motivated, as well as still feeling part of the hotel operations. This feeds into the idea that through getting team members involved and excited about something (Labovitz, 2004), they are more aligned and determined to reach the goal set out. Kaplan & Norton (2006) found that strategic employee alignment allows organisations to respond effectively to its external environments. The leaders also had to be willing to change to adapt to the current situation “You are not being a leader, if you are not willing to change, why would your team change if you are hostile towards it” (LM4). Teams benefit from leaders who can coordinate and change team members' attitudes and actions into aligned action, improving the business's efficiency and effectiveness (Yukl, 2012). The specific roles of team members within an organisation in making it ‘come alive’ is vital, and this will be more important than ever, once travel slowly resumes. The positive experiences that team members can leave on guests, can have greater impact than a well-planned marketing strategy.

Most of the participants stated that their organisations were strategically aligned pre-pandemic, and that this is the reason that they have made it through the current situation so successfully: “you can’t go through something like we did last year, and then come back and react like we did over the summer, without everyone being aligned to one goal – it wouldn’t have worked if we weren’t” (LM1). However, they also added that due to their existing alignment and the way managers handled the current situation, have aligned their teams in ways they did not think it was possible: “…we worked together as one team, rather than individual departments” (LM9). Other managers mentioned similar scenarios, showing the practices they had put in place during the first lockdown had been successful and enabled the hotel to work efficiently and effectively, once rules lifted for the summer. However, LM1 and LM2 noted that due to the consecutive three lockdowns, team members may not return as aligned as they did last time.

Table 2 below provides a summary of this study’s findings organised by themes.

Table 2: Summary of findings

|

Theme 1: Creating Strategic Alignment |

Communication: All 12 managers emphasised the key to tackling this difficult year and keeping staff aligned, being clear and effective communication. Culture: The theme of a strong culture pre-pandemic emerged in 8/10 interviews being another reason that managers were able to foster team alignment throughout the pandemic. Strong leadership: Four luxury GM’s discussed in detail about their strong senior management teams and their trust in them when keeping their own departmental teams aligned throughout the past year.

|

|

Theme 2: Managing the Crisis |

Keeping teams engaged: Team members have spent the majority of the past year away from work, and isolated at home. All 12 managers discussed the activities put in place e.g., cooking classes, quizzes and fitness sessions in order to create. Encouraging creativity and innovation: Projects were set, and team members were given specific responsibilities, to foster creativity and innovation within teams. This allowed them to be a part of something, as well as preparing them for when the hotels reopened. Frequent contact: All managers discussed weekly zoom meeting to keep their teams updated with what is going on with their hotels, the word transparency was used frequently, and managers felt it important that their teams were informed at every step. Maintaining mental health: Mental health has been on the rise in the past year due to employee anxieties, through fear for the future. The managers placed emphasis on the above findings as well as welfare calls and paying attention to spot team members that may not seem themselves. “family” theme: 7/12 of the managers referred to their teams as family and discussed a positive of this time allowing them to get to know their teams better, which they believe will create even stronger team alignment in the future. Two managers even commented that this was already evident when teams returned in the summer after the first lockdown. |

|

Theme 3: Managers encouraging proactive change |

Having the correct leaders in place: The past year required managers who were proactive and willing to change, therefore inspiring and encouraging their teams to do the same. Managers staying strong: A few of the managers commented on finding it difficult to stay strong for their teams at times, however being open in order to connect further with their teams. Managerial confidence: The managers within the study have showed great resilience in the past year, majority of them showing confidence and using this as an opportunity to better themselves and their hotels. Opportunities: The majority of managers decided to take this time as an opportunity, rather than focusing on the negatives. They carried out training and development of their teams, helped the community and encouraged staff to participate and getting the hotel ready for re-opening.

|

5. CONCLUSION

The key findings of this study (Table 2) are in agreement with the existing literature (i.e. Khadem 2008; Jackson & Schuler, 1995; Yukl, 2012) and emphasise on the importance of team member alignment for organisations to be successful. More specifically, it was found that organisational culture, communication and leadership are key factors that contribute towards the creation of team alignment during a crisis. In addition, this study considered the above areas from the perspective of luxury hotel managers and focused on how their teams were supported during the crisis; based on the existing literature this is a topic area that has not been studied before.

This study allowed the exploration of luxury hotel managers’ efforts to create alignment between their team members and the hotel unit during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a means to successful recovery. The managerial implications of this study suggest that, through the alignment of team members, organisations can create preparedness for future crises as well as staff loyalty and resilience. The role of the senior management (especially the establishment’s General Manager), is pivotal in these efforts. The achievement of teams’ alignment can also result to great levels of customer satisfaction and increased revenue for the business when travel resumes. This study also provide evidence on the various challenges faced during the crisis, and the required course of action on behalf of the management teams, in order to achieve teams’ alignment with the organisational goals.

As with any other study, there are limitations in terms of sample size, geographical location, and duration of this study. Future studies can investigate this topic area in the wider hospitality industry (i.e. restaurants, cruise ships, casinos, etc.) in different countries and cultural contexts.

References

Altinay, L., Paraskevas, A., & Jang, S.S. (2015), Planning research in hospitality and tourism, London: Routledge.

Baum, T., Mooney, S.K.K., Robinson, R.N.S. and Solnet, D. (2020), ‘COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce – new crisis or amplification of the norm?’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(9), pp.2813-2829.

Bharwani, S., & Jauhari, V. (2017), ‘An exploratory study of competencies required to cocreate memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry’. In V., Jauhari, (Ed), Hospitality marketing and consumer behavior (pp.159-185). Waretown (NJ): Apple Academic Press.

Bipath, M. (2007), The dynamic effects of leader emotional intelligence and organisational culture on organisational performance, DBL thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria.

Blayney, C., & Blotnicky, K. (2010), ‘The impact of gender on career paths and management capability in the hotel industry in Canada’, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 9(3), pp.233-255.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006), ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), pp.77-101.

Breier, M., Kallmuenzer, A., Clauss, T., Gast, J., Kraus, S., & Tiberius, V. (2021), ‘The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102723.

Brem, A., Puente-Diaz, R., & Agogué, M. (2016), ‘Creativity and innovation: State of the art and future perspectives for research’, International Journal of Innovation Management, 20(04), 1602001.

Campbell, S. (2014), ‘What is qualitative research?’ Clinical Laboratory Science, 27(1), p.3.

Carlsen, B. & Glenton, C. (2011), ‘What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies’, BMC medical research methodology, 11(1), pp.1-10.

Chi, C.G. & Gursoy, D. (2009), ‘Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(2), pp.245-253.

Darvishmotevali, M. & Ali, F. (2020), ‘Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102462.

Evans, C. (2021), ‘Covid and jobs: Why are hospitality workers leaving the industry?’ Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-57241370 (Last accessed, 23/5/2021)

Filimonau, V., Derqui, B. & Matute, J. (2020), ‘The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational commitment of senior hotel managers’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102659.

Flick, U. (2018), An introduction to qualitative research, London: Sage.

Fonvielle, W. & Carr, L.P. (2001), ‘Gaining strategic alignment: making scorecards work’, Management accounting Quarterly, 3, pp.4-14.

Giousmpasoglou, C. (2019), ‘Factors affecting and shaping the general managers’ work in small-and medium-sized luxury hotels: The case of Greece’, Hospitality & Society, 9(3), pp.397-422.

Giousmpasoglou, G., Marinakou, E. and Zopiats, A. (2021), ‘Hospitality managers in turbulent times: the COVID-19 crisis’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), pp.1297-1318.

Harding, T. & Whitehead, D. (2020), ‘Analysing data in qualitative research’. In Z., Schneider & D., Whitehead (Eds), Nursing & Midwifery Research: Methods and Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice (pp.141-160), 4th Edition, London: Elsevier

Hilliard, T. W., Scott-Halsell, S., & Palakurthi, R. (2011), ‘Core crisis preparedness measures implemented by meeting planners’, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(6), pp.638-660.

Hughes, D. J., Furnham, A. & Batey, M. (2013), ‘The structure and personality predictors of self-rated creativity’, Thinking Skills and Creativity, 9, pp.76-84.

Hughes, D.J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018), ‘Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations’, The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), pp.549-569.

Israeli, A., Mohsin, A. & Kumar, B. (2011), ‘Hospitality Crisis management practices: The case of Indian luxury hotels’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30 , pp.367-374.

Jackson, S.E. & Schuler, R.S. (1995), ‘Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments’, Annual review of psychology, 46(1), pp.237-264.

Jones, P. & Comfort, D. (2020), ‘The COVID-19 crisis and sustainability in the hospitality industry’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(10), pp.3037-3050.

Jorfi, H., Jorfi, S., Fauzy, H., Yaccob, B. & Nor, K.M. (2014), ‘The impact of emotional intelligence on communication effectiveness: Focus on strategic alignment’, African Journal of Marketing Management, 6(6), pp.82-87.

Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2006), Alignment: using the balanced scorecard to create corporate synergies, Boston: Harvard Business School

Khadem, R. (2008), ‘Alignment and follow-up: steps to strategy execution’, Journal of Business Strategy, 29(6), pp.29-35.

Kim, S. S., Chun, H. & Lee, H. (2005), ‘The effects of SARS on the Korean hotel industry and measures to overcome the crisis: A case study of six Korean five-star hotels’, Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism research, 10, pp.369-377.

Kim, W.C. & Mauborgne, R. (2009), ‘How strategy shapes structure’, Harvard Business Review, 87(9), pp.72-80.

King, N. (2004), ‘Using Templates in the Thematic Analysis of Text’. In C.. Cassell & G.. Symon (Eds), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp.256-270), London: Sage

Labovitz, G.H. & Rosansky, V. (1997), The power of alignment: How great companies stay centred and accomplish extraordinary things, New York: Wiley.

Labovitz, G.H. (2004), ‘The power of alignment: how the right tools enhance organisational focus’, Business Performance Management, 6(5), pp.30-35.

Le, D. and Phi, G. (2020), ‘Strategic responses of the hotel sector to COVID-19: Toward a refined pandemic crisis management framework’, International journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102808.

Lee, C., Hallak, R. & Sardeshmukh, S.R. (2019), ‘Creativity and innovation in the restaurant sector: Supply-side processes and barriers to implementation’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 31, pp.54-62.

Marinakou, E. (2014), ‘Women in hotel management and leadership: Diamond or Glass?’ Journal of Toursim and Hospitality management, 2(1), pp.18-25.

Mayo, A.T. (2020), ‘Teamwork in a pandemic: insights from management research,’ BJM Leader, 4, pp.53-56.

Middleton, P. & Harper, K. (2004), ‘Organisational alignment: a precondition for information systems success?’ Journal of Change Management, 4(4), pp 327-338.

Novelli, M., Burgess, L.G., Jones, A. & Ritchie, B.W. (2018), ‘‘No Ebola… still doomed’–The Ebola-induced tourism crisis’, Annals of Tourism Research, 70, pp.76-87.

Paraskevas, A. & Quek, M. (2019), ‘When Castro seized the Hilton: Risk and crisis management lessons from the past’, Tourism Management, 70, pp.419-429.

Paraskevas, A., Altinay, L., McLean, J. & Cooper, C. (2013), ‘Crisis knowledge in tourism: Types, flows and governance’, Annals of Tourism Research, 41, pp.130-152.

Pongatichat, P. & Johnston, R. (2008), ‘Exploring strategy‐misaligned performance measurement’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 57(3), pp.207-222.

Qu, S.Q. & Dumay, J. (2011), ‘The qualitative research interview’, Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 8(3), pp.238-264

Ritchie, B.W. & Jiang, Y. (2019), ‘A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management’, Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102812.

Robinson, A.G. & Stern, S. (1997), Corporate Creativity - How innovation and improvement actually happen, San Francisco (CA): Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Rodrigues, J. & Kumar, K. (2020), ‘Impact of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry and its effect on audit’. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/xe/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/the-grind /impact-covid-19-hospitality-industry-effect-audit.html (last accessed 27/5/2021).

Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J. & Bausch, A. (2011), ‘Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs’, Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), pp.441-457.

Rosing, K., Frese, M. & Bausch, A. (2011), ‘Explaining the heterogeneity of the leadership-innovation relationship: Ambidextrous leadership’, The Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), pp.956-974.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2009), Research methods for business students. London: Pearson education.

Schneider, B., Godfrey, E.G., Hayes, S.C., Huang, M., Lim, B., Mishi, L.H., Raver, J,L. & Ziegert, J.C. (2003), ‘The human side of strategy: employee experiences of strategic alignment in a service organisation’, Organisational dynamics, 32(2), pp.122-141

Serfontrin, J.J. (2009), The impact of strategic leadership on the operational strategy and performance of business organisations in South Africa, DBM thesis, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch.

Speakman, M. & Sharpley, R. (2012), A chaos theory perspective on destination crisis management: Evidence from Mexico, Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 1(1-2), pp.67-77.

Thorne, S. (2000), ‘Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence-based nursing’, 3(3), pp.68-70.

UNWTO. (2020), International Tourism and COVID-19. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/ international-tourism-and-covid-19 (last accessed 22/5/2021).

Vehovar, V., Toepoel, V. & Steinmetz, S. (2016), ‘Non-probability sampling’, The Sage handbook of survey methods, pp.329-345.

WHO, (2020), ‘Operational considerations for COVID-19 management in the accommodation sector: interim guidance’. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331937 (last accessed 20/5/2021).

Wong, K.F.W., Kim, S., Kim, J. & Han, H. (2021), ‘How the COVID-19 pandemic affected hotel employee stress: Employee perceptions of occupational stressors and their consequences’, International Journal of Hospitality management, 93, 102798

Yukl, G. (2012), ‘Effective leadership behaviour: What we know and what questions need more attention’, Academy of management perspectives, 26, pp.66-85

Zaccaro, S.J. & Klimoski, R. (2002), ‘Special issue introduction: The interface of leadership and team processes’, Group and Organisation Management, 27, pp.4-13.