NAUTICAL TOURISM: CONTRIBUTION TO SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEVELOPMENT

Eunice R. Lopes1, 2; Maria R. Nunes1; Jorge Simões3; Júlio Silva4; João T. Simões1,5 Manuel Rosa6; Carla Rego7; Joana Santos8

1Polytechnic Institute of Tomar & Techn&Art. Departmental Unit Social Sciences, Tomar, Portugal

2 CiTUR-IPL; CRIA-FCSH-UNL; GOVCOPP-UA; Portugal

3Polytechnic Institute of Tomar & Techn&Art. Departmental Unit Business Sciences, Tomar, Portugal

4Polytechnic Institute of Tomar & Techn&Art. Departmental Unit Information and Communication Technologies, Tomar, Portugal

5Ui&D-ISLA, Portugal

6 Polytechnic Institute of Tomar & Techn&Art. Departmental Unit Engineering Tomar, Portugal

7Polytechnic Institute of Tomar & Techn&Art. Departmental Unit Archeology, Conservation and Restoration and Heritage, Tomar, Portugal

8 Intermunicipal Community of Médio Tejo, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Nautical tourism developed through the water-river resource is fundamental for the consolidation of tourism products. According to the Tourism Strategy 2027, water is considered one of the six differentiating assets of the destination Portugal, emerging as a priority element of intervention and of extreme relevance to the territory, given that water constitutes the support of unique assets located in the great majority of the interior of the country and with tourist potential (Portugal, 2017). This strategy also favors, among other elements, energy efficiency, environmental certification, and the adoption of international quality standards. The 2030 Agenda: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also reinforces actions that aim to protect and safeguard cultural and natural heritage. Consequently, nautical tourism emerges as a relevant product that dynamizes the territory, in which the river is crucial for the valorization of the tourist practice and for the sustainable management of the territory.

This article aims to highlight nautical tourism, in its relationship with territorial tourist practices, and to understand the ways of implementing sustainability dynamics in the context of cultural and environmental impacts. Based on an exploratory approach, it was designed to analyze the information contained in official tourism sites limited to the territory of the Médio Tejo. Through the identification and interpretation of the relationship between the potential and the valorization of the patrimonial and water resources, the results of this study, allowed to perceive the practice of a tourism based on the precepts of sustainability, above all, in the cultural and environmental dimensions. This fact demonstrates a favorable territory for the nautical tourism segment.

Key Words: Nautical Tourism, Sustainable Development, Cultural and Natural Heritage

1 INTRODUCTION

Nautical tourism is one of the segments of tourism activity recognized by the Tourism of Portugal as the enjoyment of water-related travel, and all types of nautical activities can be practiced, whether in leisure or competition. Nautical tourism includes all types of water-related activities, with sport and leisure practices also included (Figueiredo & Almeida, 2017). According to the Directorate General for Sea Policy, boating is divided into recreational and sport, and is directly linked to recreational boats. Although it is common to associate water sports and tourism with any model of boat, it is possible to verify the existence of various activities, such as diving, underwater hunting or coasteering. These activities can also be framed in the type of boating that does not directly require the use of boats to carry it out.

Nautical tourism is related to the act of navigating in an aquatic environment and can be classified as: fluvial; maritime, dams, lakes (Silveira, 2016). The existence of a relationship between nautical tourism and water sports is evident in the fact that maritime tourism includes recreational activities that involve travel away from home and focus on the marine environment (Orams, 1999). Considering in this dynamic, also the companies that work in the same scope (construction sites, resorts on the coast, among others).

Recreational boating enthusiasts will find in Portugal sea and river suitable for sailing. Portugal has places considered as some of the best regatta fields in the world, leading to the recurrent organization of events and championships. Portugal has been affirming itself as a tourist destination of excellence due to its culture, geographical location, climate, and the safety that it conveys to tourists. With these characteristics, Portugal has won two awards related to nautical tourism, being the main cruise destination in Europe 2020 (Lisbon) and the leading Cruise Port in Europe in 2020 (Lisbon Cruise Port).

According to recent data, Portugal recorded an increase of 7.9% compared to 2018, i.e., the number of arrivals to Portugal of non-resident tourists is estimated to have been 24.6 million, causing GDP to have increased by 2.2% (Instituto Nacional de Statistic, 2020).

Nautical tourism achieved prominence through cruise tourism, which recorded a decrease of 3.3% compared to the previous year, with the entry of 862 cruise ships in the main ports of the country (Instituto Nacional de Statistic, 2020).

The Strategic Plan 2027 (Portugal), refers to water as differentiating strategic assets, contextualizing them as rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and thermal waters of recognized environmental quality. Also, the existence of several river beaches throughout the country (overall: 115), supports the implementation of infrastructures that contribute to the growing demand for nautical tourism.

In Portugal, the Tourism Strategy 2027 developed lines of action focused on nautical tourism highlighting its importance for the enhancement of the territory and communities, to affirm tourism in the economy of the sea. These lines of action include a) strengthening Portugal's position as a destination for nautical, sporting and leisure activities associated with the sea, along the entire coast and as an international surfing destination of reference; b) enhancing the infrastructure, equipment and support services for nautical tourism (ports, marinas and nautical centers); c) integrating products into the sustainability of nautical culture; d) boosting "experience routes" and tourist offers around the sea and nautical activities; e) requalifying the coastlines and enhancing beaches. Another highlight is the development and improvement of navigation systems, for safer river navigation, improving quays and creating mooring platforms for recreational boats or support infrastructures (Portugal, 2017).

In this context, environmental issues have also achieved a relevant role in society, and the tourism sector has been pressured to analyze the environmental, cultural, social, and economic indicators in the logic of sustainability of tourist destinations. Here is integrated tourism planning as fundamental, as a manager of supply and demand elements, satisfying tourists, but at the same time promoting “a responsible or alternative tourism” (Martins, 2012). Tourists have been changing their motivations when enjoying the tourist destinations, tending to have more ecologically conscious behaviors, basing their search for quality and existing natural, cultural, and traditional resources.

Nautical tourism presents itself as a favorable segment for society in terms of the development of natural and cultural resources. To practice this type of tourism, it is necessary for the marine and riverine environment and structures to have accessibility conditions conducive to its development.

This factor contributes to the supply of tourist activities linked to nautical tourism practices and the consequent increase in the quality of tourist destinations, which must be anchored in sustainable tourism development.

2 NAUTICAL TOURISM - CHARACTERIZATION OF THE MÉDIO TEJO REGION

When we talk about nautical tourism in central Portugal, the anchor resource that inevitably comes to mind is the Castelo do Bode reservoir (Portugal). This reservoir was built following the completion of the Castelo do Bode dam in 1951 and is one of the oldest and most important infrastructures in Portugal, not only because of its hydroelectric function, which, among other things, supplies the capital (Lisbon), but also because of its imposing concrete wall, which gives rise to one of the largest artificial lakes in the country.

The immensity and imposing size of the lake, associated with the undeniable scenic beauty of its natural surroundings and its orographic location itself, which divides the region in half, make it one of the most important elements of identity for the Médio Tejo region, as well as being one of the iconographies most associated with the image that many people have of the central interior of the country. It is an attraction, partially worked and adapted to host some seasonal activities such as “wakeboarding, windsurfing, sailing, rowing, jet skiing, motor boating and sport fishing (trout, achigã, eels, red crayfish)” (Turismo Centro de Portugal, 2021), and others that take place on land, in the proximity of the water, such as hiking and mountain biking on approved routes (such as the GR33 of Zêzere) or on natural trails and local paths. It should be noted that Albufeira has some motorized leisure boating associated with river dynamics, such as the tourist boat “São Cristóvão”, and other leisure boats, which through the existing nautical centers and wharfs, allow you to get to know the emblematic corners of Albufeira through tranquil cruising.

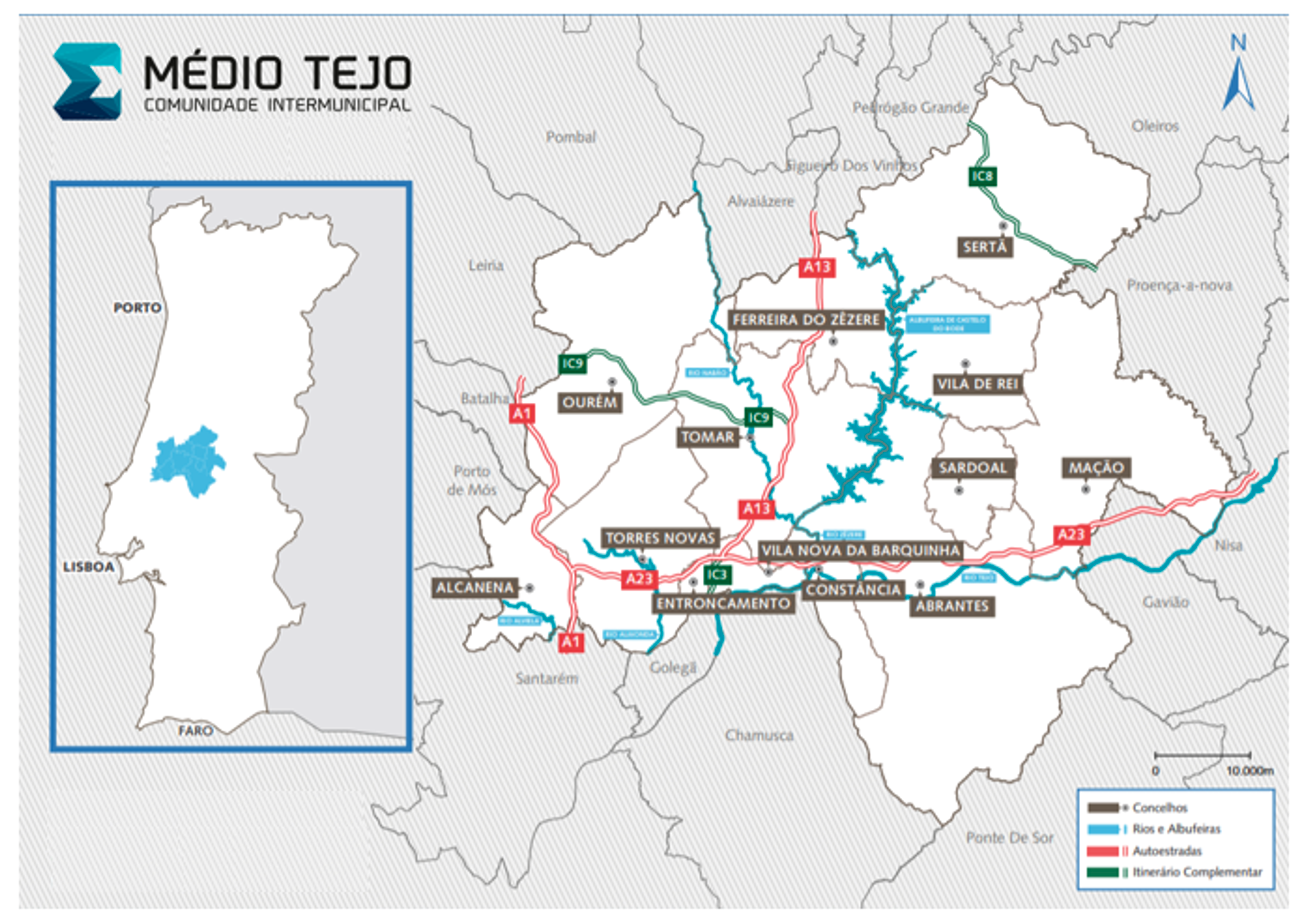

Due to its important architectural and engineering work, a visit to the inside of the dam is also another recommended educational experience. Although it still presents an enormous potential for the creation of new projects in the field of tourism. Mainly because, with an area of about 33 km2, and covering a considerable part of the hydrographic basin of the Zêzere River, which has a length of 60 km (30% of the total length of the Zêzere River), it integrates seven municipalities: Figueiró dos Vinhos, in the Leiria Region, at the northern limit; and six municipalities integrating the Médio Tejo Region: Sertã, Vila de Rei, Ferreira do Zêzere, Sardoal, and also Abrantes and Tomar at the southern limit (Figure 1) and, therefore, it should be noted that its area of natural, environmental and economic influence of the reservoir goes beyond the dam itself and the seven identified municipalities: the bed of the Zêzere River, the hydroelectric exploitation (and the respective discharges carried out), as well as the support services, and also the existing accessibility network, which determine that its influence extends even along the last 12 kms of the Zêzere River before it flows into the Tagus River, also involving in this path the municipalities of Vila Nova da Barquinha and Constância.

The reservoir, which is part of NUT III – Médio Tejo, was classified as protected by Regulatory Decree no. 2/88, of 20th January. Thus, the reservoir and its direct influence territory are covered by the Plano de Ordenamento da Albufeira de Castelo do Bode (Plano de Ordenamento da Albufeira de Castelo do Bode - POACB), whose revision was approved by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers no. 69/2003, and which covers the water plane and its protection zone with a maximum width of 500 m, covering an area of 14 273ha. The maximum storage capacity of the reservoir is 1 100 hm3 and its floodable area at full storage extends to 3 300ha.

Figure 1 Geographic location of the Médio Tejo.

Source: General Directorate of the Territory (DGT) / Inter-municipal Community of the Médio Tejo (CIMT); Topographic Base MNT of SCN10K; National Statistics Institute (INE) - Censuses 2011.

Protected by its own management plan, its management includes rules and standards of good sustainable practices regarding the use of the water plane and the area around the lake, to safeguard the quality of natural resources, especially water.

In this sense, with a view to boosting nautical tourism in the Médio Tejo region, the Médio Tejo Intermunicipal Community (CIMT) has played an important role in the environmental and tourism valorization of this lake. One of the best examples of the new dynamics that the Albufeira de Castelo do Bode has seen is based on the wakeboarding activity and the investment led by the CIMT in cable park equipment installed in five places in the Albufeira, which allow its practice in a more controlled and accessible way to all practitioner profiles (from beginners to professionals), thus responding to the environmental preservation challenges imposed by the POACB, and generating new tourism development opportunities (Médio Tejo, 2021). The creation of the world's first wakeboarding resort, generating its own infrastructures in five river beaches of Castelo do Bode, in a partnership involving, among other entities, the municipalities of Abrantes (Aldeia do Mato), Tomar (Montes), Ferreira do Zêzere (Lago Azul), Sertã (Trízio) and Vila de Rei (Fernandaires), was one of the goals achieved.

In an area of 30 km, the five beaches are equipped with cable parks, consisting of a cable connecting the two banks and which will allow the practice of wakeboarding without the help of a boat and, therefore, without the environmental impact associated with the use of motorboats. Equally aware of the importance of sustainable tourism, one of the main priorities of the Intermunicipal Community of the Médio Tejo (CIMT), also involves the creation of the Castelo do Bode Nautical Station (ENCB), with a view to the environmental and tourist valorization of this reservoir, based on a strategy of integrated tourist promotion.

The Castelo do Bode Nautical Station (ENCB) project began as part of a national process aimed at the development, promotion, and certification of Nautical Stations in Portugal, which was implemented by Fórum Oceano, member and representative of Portugal, with FEDETON (Management entity of the International Network of Nautical Stations). In this sense, the Intermunicipal Community of Médio Tejo (CIMT), presented in June 2018, an application with a view to the creation and certification of the Castelo do Bode Nautical Station. The Castelo do Bode Nautical Station (ENCB), focused on the nautical tourism offer that the Castelo do Bode Lagoon allows to offer, involves the following municipalities: Abrantes, Ferreira do Zêzere, Sertã, Tomar and Vila de Rei, which are articulated on the ground with three Local Action Groups (LAGs): Association for the Integrated Development of Ribatejo Norte (ADIRN), whose action extends in the territory from Alcanena to Ferreira do Zêzere, Ourém, Tomar, Torres Novas and Vila Nova da Barquinha; Association For The Integrated Development of Ribatejo Interior (TAGUS), involving Abrantes, Constância and Sardoal and the Development Association of Pinhal Interior Sul (Pinhal Maior), integrating Mação, Oleiros, Proença-a-Nova, Sertã and Vila de Rei.

Recognizing the potential that the Middle Tagus region has in the area of nautical tourism, the future of this tourism product involves the creation of a quality tourism supply network, structured on the basis of the valorization of the nautical resources present in the area, as well as the complementary supply (accommodation, catering, nautical activities and other relevant services and initiatives to attract tourists and other users), adding value and creating diversified and integrated experiences.

Thus, the aim of this Nautical Station is to help establish a nautical hub of excellence centered on the Castelo do Bode lagoon and nautical activities, benefiting and integrating the regional landscape and cultural surroundings, cooperating to create a brand linked to the lagoon, differentiating the region, and promoting the economic, social, and sustainable development of the Médio Tejo region.

3 TOURIST PLANNING: IMPACTS OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND CULTURAL TOURISM

According to Santana (2009) and Jordão (2019), tourism impacts are referred to as "the trail left by both the tourist and the associated infrastructure in the environment transformed into a tourist destination. Associated with the development of tourism is a diverse and complex set of impacts. Tourism activity can generate various benefits and damages for a given region, and these impacts can occur mainly at the economic, social, cultural, and environmental levels (Eusébio & Carneiro, 2012¸ Jordão, 2019). Therefore, the impacts, mentioned above, can affect the receiving communities, as well as the ones that send tourism, but the intensity, suffered, is greater in the resident communities in tourist destinations (Eusébio & Carneiro, 2012; Jordão, 2019). Aiming at better planning and better management of the activity, one should try to understand and analyze, in a careful way, the impacts of tourism, both negative and positive, to develop plans and actions aimed at minimizing their costs and, at the same time, maximize their benefits (Marins, Mayer & Fratucci (2015); Jordão, 2019).

Thus, according to the authors mentioned, considering the size of the tourism phenomenon and its intrinsic characteristics, all dimensions should be considered, in terms of impacts generated, in its various aspects, positive and negative, seeking to contribute to a reduction in social cost, as well as the enhancement of the various socio-cultural and economic benefits of tourism. In this sense, it will be essential to carry out regular and careful analyses of its various developments, which could bring unwanted consequences if not properly managed. The characteristics of tourism activity, as well as the singularities of each receiving region, should be considered for a better tourism management and planning (Jordão, 2019).

In this context, also according to Cooper et al. (2008) and Jordan (2019), the environment, whether natural or artificial, will be the most crucial element of the tourism product. However, according to the same authors, when a tourism activity is developed, the environment will be, inevitably, altered or modified. It is understood by this, the close relationship that occurs between tourism and the environment, since all tourism activity depends on an environment for this same activity to develop. As a result, a set of factors/impacts will arise, which this same environment will suffer, depending on the tourism activity developed.

In this regard, a set of negative environmental impacts have been identified over time in relation to tourism development (Table 1).

Table 1 Tourism development: negative impacts.

|

Water pollution (rivers, lakes, oceans) |

|

Air and noise pollution |

|

The excessive increase in the production of rubbish and waste at destination |

|

The impact on and destruction of wildlife |

|

Alteration/destruction of vegetation and soil |

|

Damage to geological formations |

|

Destruction of marine ecosystems |

|

The degradation of landscapes |

|

Loss of natural landscapes (and unspoiled nature) for tourism development |

|

The use of historical heritage sites for tourism structures |

Source: Own elaboration. Adapted from Andereck et al. (2005); Cooper et al. (2008); Eusebio & Carneiro (2012) and Jordão (2019).

Tourism, when well-planned and managed, may promote exactly the opposite, i.e., more specifically, the revaluation and preservation of natural areas, through the creation of entities and conservation units and also through the awareness of residents and visitors, as well as develop improvements, at structural level, that help preserve the environment, giving as examples sewage networks and leisure spaces that do not harm nature; as well as promoting the preservation and rehabilitation of cultural heritage (Davidson & Maitland (1997); Lage & Milone (2001); Cooper et al. (2008) and Jordão (2019).

Regarding socio-cultural impacts, according to Hall (2004), these began to hold greater relevance to the development of tourism activity, since, at the time, it was understood that although it is difficult to quantify the social impacts of tourism, these may be the most relevant indicator of tourism development. Following on from this, social impacts are considered essential, not only from the ethical point of view of the need for community involvement in decision-making processes, but also because without them, tourism growth and development may become increasingly difficult to monitor.

There are socio-cultural impacts considered to be more positive in tourism (Table 2). However, in opposition, residents also identify several negative socio-cultural effects of tourism (Table 3).

Table 2 Positives. Table 3 Negatives.

|

The enhancement of cultural heritage |

|

At the level of moral conduct |

|

The enhancement and promotion of traditions |

|

Housing-related problems |

|

The promotion of diversity and cultural exchange |

|

Negative changes in values and customs |

|

The rejuvenation of traditional arts and crafts |

|

The commercialisation of local cultural arts and rituals |

|

Conservation of the built heritage |

|

Loss of authenticity of local culture |

|

Increasing the offer of cultural events |

|

Changes in the configuration and aesthetics of traditional areas |

|

Improving the quality of life |

|

At the level of moral conduct |

Source: Own elaboration. Adapted from Andereck et al. (2005); Cooper et al. (2008); Eusebio & Carneiro (2012) and Jordão (2019).

Thus, the various impacts must be analyzed, in an integral and participatory manner, with a view to giving visibility to all those involved, whether affected or representative, with a view to a correct understanding and, consequently, correct planning of sustainable tourism development in destinations.

3.1. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

Recreation and leisure are one of the tourism sectors. This sector includes the nautical tourism segment. As in other segments of the tourism sectors, on the one hand, there is consumption of resources, including: electricity, gas, fuel, lubricants, water, food, plastic, glass, and cardboard packaging of various products such as drinks or cleaning products. On the other hand, activities arising from the maintenance of services and the use of leisure facilities or associated equipment such as restaurants, gyms, and swimming pools, produce solid waste, organic waste from catering, wastewater, water contaminated with fuel and lubricating oils, aerosols, batteries, light bulbs, printer cartridges and wastepaper, plastic and glass packaging.

If hotel units are associated with nautical tourism, water, chemical products and energy consumption for air conditioning, lighting and ventilation increase exponentially, especially about water consumption for bathing, cleaning, laundry and maintenance of gardens and other green areas. The strong per capita water consumption is known and studied whenever, associated with tourism, there are hotel units, when compared to the typical consumption of the surrounding rural areas (Gössling, 2002; Johnson et al, 2012; Graci & Kuehnel, 2021). The impact associated with these activities is important from the point of view of natural resource consumption and may even cause water stress in the water catchment. The extent of the resource flows and the products resulting from the consumption and use of these resources largely define the extent of the environmental impacts associated with nautical tourism activities.

Regarding nautical tourism in particular, the effect of the environmental impacts caused by the activities developed can be drastically reduced if some of the aspects linked to the consumption and products of this practice are properly managed. The fact that tourism activities are located near large dimensions of water means that, with investment in equipment, water from a dam, a lake, a river or even sea water can be captured and treated to replace the use of water from the public network or from underground catchment. This water can be used for irrigating green spaces, filling swimming pools, washing and laundry. Main’s water can eventually be used only for cooking and bathing, but if the quality of purification of the local catchment is sufficient, this water can totally replace external water supplies. In addition to the collection and treatment of adjacent water, there should be careful management of expenditure, using timed taps and showers, maintaining taps to avoid leakage, building underground tanks to collect rainwater and bath water, which can be used for irrigation, and adapting irrigation times to the daily weather and off-peak hours.

Regarding the problem of wastewater, it is not possible to license projects that do not contemplate the collection of the waters accumulated in septic tanks or their local treatment so that the quality indicators respect the values published in the legislation before being looped in the reception basin. The energy issue is quite important, especially regarding lighting. Energy sources should tend to be alternative, namely solar and wind. This strategy improves the efficiency of the use of natural resources. In the case of consumption, lighting is a type of consumption that can be reduced using timed lamps that turn on when movements are detected. It is a very rewarding strategy during the night periods when there is little movement in the support facilities or even inside the hotel unit. The most important energy consumption is associated with air conditioning and therefore this aspect of energy consumption should have a centralized management that is adapted to the climatic and meteorological conditions.

The reduction of waste impacts should be mainly analyzed from the perspective of organic waste from the kitchen and restaurant and from the perspective of packaging waste. In consumption, it is important to reduce the volume of paper, plastic, and glass packaging. In the case of plastics, it is advisable to buy larger containers rather than small containers with the capacity of those used in households. If cleaning products are purchased in larger reusable containers, and cleaning products are distributed to cleaning staff in small reusable containers, in addition to optimizing costs, the amount of waste from plastic containers is reduced. From the point of view of the waste generated and its impacts, it is very important that there are Eco points and undifferentiated waste containers in public areas where visitors and services can place undifferentiated waste and all packaging waste for recycling. Regarding undifferentiated waste, if organic waste is carefully separated, it can be composted to produce fertilizer for the green areas of the facilities.

There is clear conformity in what should be the key elements for low-impact sustainable tourism facilities. The various models and guidelines outlined highlight that, above all, development, on any scale, should be framed within and respectful of the natural and cultural environment in which it is situated (Beyer et al, 2005).

In the case of accommodation, ecotourism and eco-lodges represent realities in which enormous attention is paid to the premises of sustainable tourism. Tourism developments set in the heart of nature and on riverbanks should seek to optimize the management of waste produced and the resources associated with cultural and environmental heritage and populations (Osland & Mackoy, 2004).

In this sense, the practice of nautical tourism and all associated services require tourism planning so that environmental issues and their impacts prevent the sustainability of the territory.

3.2. CULTURAL AND HERITAGE IMPACTS

The planning of nautical tourism should consider the cultural and heritage sector. Although there may be fewer positive impacts, as mentioned above through the research carried out by Andereck et al. (2005); Cooper et al. (2008); Eusebio & Carneiro (2012) and Jordão (2019), it is considered that if there is sustainable planning, tourism can promote the dissemination, safeguard and even conservation of tangible or intangible heritage resources.

Nautical destinations, specifically those that are distant from urban centers or villages, even if sometimes they are not integrated in places with built heritage, are not alien to it. The visitors to these tourist destinations also have other interests, such as gastronomy and participation in cultural events where the heritage identity of the territory is present. Each water sports center is part of a region that has its own values and identity which distinguishes it from other regions, and heritage values are of great importance for the perception and understanding of this territory.

The cultural heritage of the region covered by the five river beaches of the Médio Tejo is vast, and in this context, not only the heritage that is closest to it, but also that which is found within the same municipality (Table 4).

Table 4 Classified cultural heritage.

|

Aldeia do Mato (Abrantes)

|

- Nossa Senhora da Esperança Church and Convent - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1977. - São Vicente Church - Classified as National Monument since 1926. - Palacete dos Albuquerques - Classified as Municipal Value in 1977. - Santa Maria do Castelo Church/Museum of D. Lopo de Almeida - Classified as National Monument since 1910. - Abrantes Fortress - Classified as a Public Interest Site since 1957. - São João Baptista Church - Classified as National Monument since 1948. - Misericórdia Church and Hospital in Abrantes - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1977. - Set of Pillars or Moors - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1970. - Ethnographic Museum of Martinchel. - In the parish of Aldeia do Mato, where the river beach is located, you can also find the Parish Church of Santa Maria Madalena, the Church of Sagrado Coração de Maria and the Fountains of São João and São José. |

|

Fernandaires (Vila de Rei)

|

- Misericórdia Church. - Nossa Senhora da Conceição Church (Matriz)São João Baptista Church. - Chapel of Christ the King - Manor House. - Parochial Museum. - Roman bridge of Isna. - Roman bridge in Vale da Urra. - Municipal Museum of Vila de Rei. - Geodesy Museum - Geodesic Centre of Portugal. - Fire and Resin Museum. - Village Museum. - Museum of Adventure and Travel - trout. - Windmills. |

|

Lago Azul (Ferreira do Zêzere)

|

- Nossa Senhora da Graça Church (Areias) - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1934. - Pias Pillory - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1933. - Águas Belas Pillory - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1933. - Saint Michael Church - Parish Church of Ferreira do Zêzere. - Saint Peter of Castro Chapel (Pombeira), in the hill near the river - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1940. - Nossa Senhora do Pranto Church, located in Dornes, municipality of Ferreira do Zêzere, classified as Property of Public Interest since 1943. Its foundation is attributed to the queen Saint Isabel, in 1285, having later been rebuilt in 1453. - Dornes Tower, located next to the church in the same town, classified as Property of Public Interest since 1940. |

|

Praia dos Montes (Tomar)

|

- Convent of Christ of Tomar - Classified as World Heritage by UNESCO since 1983. - Santa Maria dos Olivais Church - Classified as National Monument since 1910. - Church of São João Baptista - Classified as National Monument since 1910. - Nossa Senhora da Conceição Church - Classified as National Monument since 1910. - São Lourenço Chapel/Patron of D. João I - Classified as National Monument since 1910. - São Lourenço Fountain - Classified as a Public Interest Monument since 1959. - Pillory of Tomar - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1933. - São Gregório Chapel - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1948. - Padrão de São Sebastião - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1959. - São Francisco Church and Convent - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1959. - Matches Museum. - Contemporary Art Nucleus. - Lagares del Rei. - Sete Montes National Forest, on the castle slope. - In the parish of Olalhas, where the river beach is located, one can also find the Igreja Matriz de Nossa Senhora da Conceição, Capela de Santa Sofia, vestiges of a fortification (the Olalhas castle), water mills and several fountains of interest: Fonte das Lameiras, 1952; Fonte do Vimieiro; Fonte dos Sombreiros; Fonte da Ribeira. |

|

Trízio (Sertã)

|

- São Pedro Church - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1974. - Misericórdia Church - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 2003. - Pillory of Sertã - Classified as Property of Public Interest since 1933. - Castle of Sertã/ Church of Saint John the Baptist. - Coat of arms houses. - Roman bridges. - Cave paintings. - Water mills and windmills. - Church and Convent of Santo António/Municipal Library-Museum. - In the parish of Palhais, where the fluvial beach is located, one can also find the Chapel of Our Lady of Nazaré. |

Source: Own preparation (2021).

There is no doubt that cultural heritage is an important resource for territorial development. The increasingly noticeable concern of the new generations towards the environment and its preservation, raises the care that planning and sustainable development have deserved in recent years regarding the practices of a responsible tourism (Lopes & Simões, 2019: 213). The development and planning instruments that should be a priority in the reaffirmation of the territory, are the spatial planning plans because they consubstantiate specific strategies on the territory grounded on the cultural heritage.

In this sense, heritage resources combined with tourism have promoted a strong component of development in the territories, allowing to draw more consistent guidelines in economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects, providing experiences to visitors and local people who interact in the cultural dynamics of the territories (Lopes, et al, 2020: 11).

The existing classified cultural heritage in the region where nautical tourism is recognized reinforces the importance of spatial planning as a tool for enhancing heritage identity and promoting sustainable territorial development.

4 PROMOTION OF NAUTICAL TOURISM DESTINATIONS

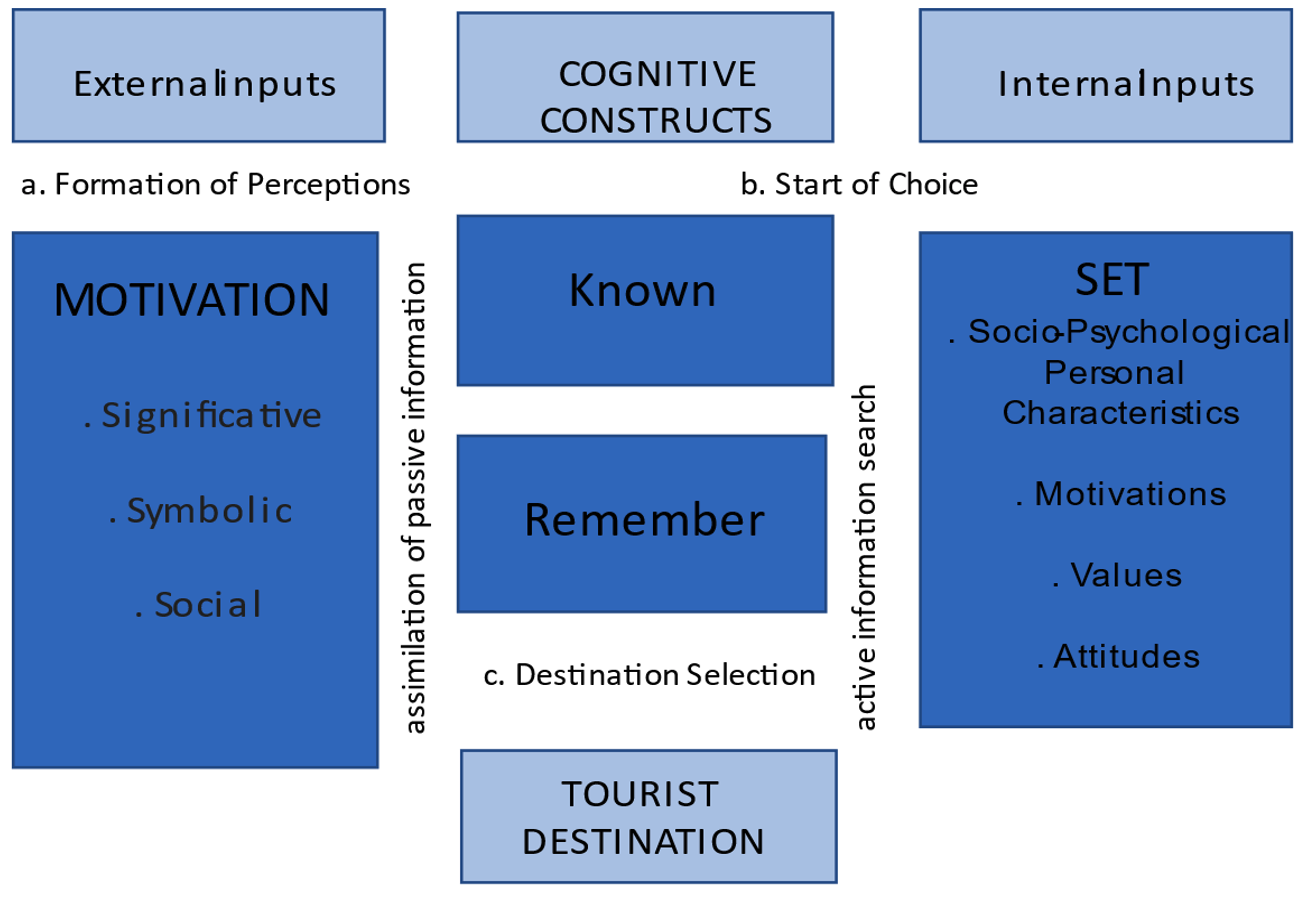

Tourism destinations can be distinguished by the image that both tourists and residents have about them as tourism spaces (Baloglu & Mangaloglu, 2001). The image affects the destination choice behavior and the tourist experience (Lee & Lee, 2009). Some destinations have specific characteristics that have a strong influence in the formation of its image (Figure 2), as is the case of the river resource, the possibility to practice nautical tourism.

In fact, tourism is a consumer industry based on images (Buck, 1993). Therefore, the perceptions of tourists and of residents can constitute a real guide for the development of destinations (Andriotis, 2005). It means that the resident population contributes to the formation of the image of destinations (Leisen, 2001).

Nowadays, interest in the enjoyment of tourism products has increased, becoming decisive for the success of tourist destinations and the local communities themselves (Crouch et al, 2004).

There is an increasing demand for remote and natural destinations (Urry, 1995), with a tendency to search for new tourism products and destinations that provide intense experiences (Stamboulis & Skayannis, 2003).

Figure 2 Travel model and choice of tourist destinations.

Source: Own elaboration. Adapted from Um & Crompton (1990).

The existing relationship between attractions of the places and tourists form the image of destinations and this representation, by its promotion, attracts tourists and visitors, producing the tourist space (Framke, 2002). It is in this sense, that tourist destinations are spaces produced by social practices of tourists that differentiate them from other places (Edensor, 1998). There is no doubt that tourist destinations are places to which people choose to travel to enjoy their specific characteristics (Leiper, 1995), as in the case of the river resource, favorable to the practice of nautical tourism.

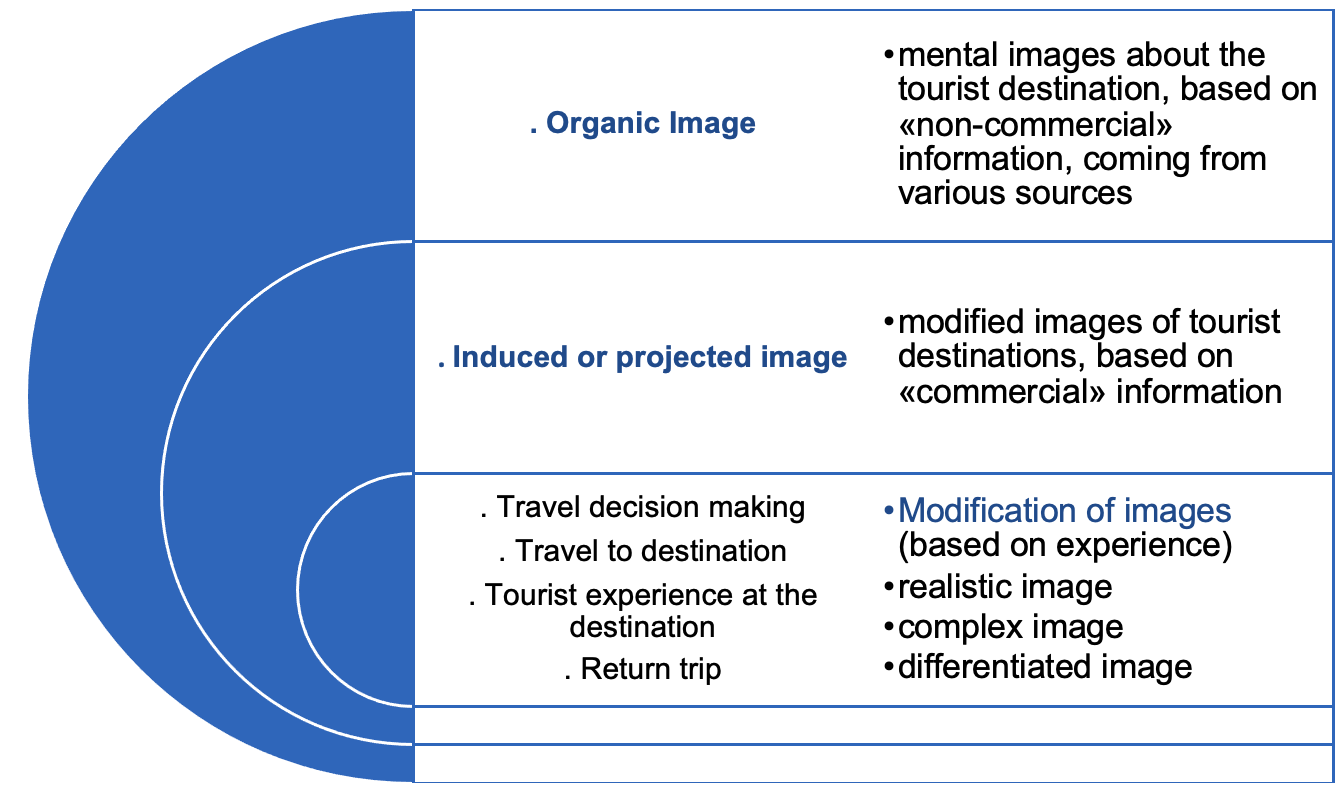

The projected images (Figure 3) can include commercial sources (e.g. travel publications and advertising) and organic sources (e.g. popular culture, media, literature and education), (Gunn, 1972).

Figure 3 Projected images of tourist destinations.

Source: Own elaboration. Adapted from Gunn, 1972.

Understanding the different images that visitors and tourists have of destinations is fundamental to understand the attributes granted to the promotion of the tourist destination. Centro de Portugal has eight Nautical Stations (Table 4).

Table 4 Nautical Stations in the Centro de Portugal.

|

Nautical Station of Aveiro

|

It is made up of local and regional partners that enhance nature sports, active tourism, and the identity of the territory, in a logic of communication and global dynamism of the spaces and nautical activities of Aveiro. |

|

Nautical Station of Castelo do Bode

|

Is a quality nautical tourist supply network, organized based on the integrated valorisation of nautical resources present in a territory (includes the offer of accommodation, restaurants, nautical activities and other activities and services), to attract tourists and create diversified experiences and integrated. |

|

Nautical Station of Estarreja

|

It is a territory markedly linked to water. It is part of the Ria de Aveiro Special Protection Zone (Natura 2000 Network), and the community has one of its identity references in this natural element. In the shipyards of the parish of Pardilhó, traditional wooden boats are created by the hands of the master carpenters. |

|

Nautical Station of Ílhavo

|

It has natural conditions of excellence for the sport and leisure of nautical. There are several sailing schools and other water sports, associated with yacht clubs and maritime-tour operators. |

|

Nautical Station of Murtosa

|

It is a station that has more than two dozen partners, between companies and institutions, with the objective of promoting and enhancing Murtosa, the geographical and affective heart of the Ria de Aveiro as a nautical tourist destination of reference, through the provision of quality integrated products. |

|

Nautical Station of West |

It is a nautical touristic offer network that aims to attract more tourists to the practice of nautical tourism. |

|

Nautical Station of Ovar

|

It is a nautical tourist supply network, centred on three main natural resources: Barrinha de Esmoriz, Mar and Ria de Aveiro. The enhancement of the existing network and resources is complemented by the integration of accommodation offer, nautical activities and other services that are relevant for attracting tourists. |

|

Nautical Station of Vagos

|

It is a station that intends to develop a transversal strategy, starting from nautical, to increase the tourist attractiveness of the Municipality and to enhance the natural and landscape heritage. |

Source: Own elaboration. Adapted from Nautical Portugal (Centro de Portugal).

The way images of the tourist destination are projected to the tourist(s), has been changed over time, the brochure, the catalogue, the tourism fairs with promotional videos, and the emergence and use of the internet, which is currently the common platform in communication and marketing mechanisms. The paradigm shift from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0, allowed to move from an internet of individual use (creation and publication) to a type of collaborative use, of constant updating. The change of this paradigm also allowed the creation of platforms, applications based on this type of concept, as well as Web 2.0 and the emergence of social networks (Kaplan & Haenlain, 2010: 60-61). Its use as a vehicle of communication and the technologies that have been growing and spreading its use, has allowed new methodologies of dissemination and promotion of tourist destinations.

The new platform allows reaching different types of audiences. The use of social networks, such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, makes it possible to reach diversified audiences.

Multimedia has been the basis of these types of platforms, the use of video and audio photographs has been the mainstay of these social media platforms. Instagram, a photo sharing platform, has evolved into a platform with video sharing and live videos. Which has been adopted by users who are looking for, more the concept of image and video and less words. The same has garnered users, tending to younger audiences, with the concept of hashtags #, which allows referencing places, people, brands, themes, sports, allowing more direct access to information when searched by hashtag (Miles, 2014: 27). Also, YouTube has more than a billion users and is used as a search engine, being the second most used after Google. One minute of video has the same impact as 1.8 million words (Freseach, 2021).

The use of digital platforms as a means of promoting destinations is fundamental in the current landscape of user demand and search, especially if they are enhanced with multimedia content such as videos. Platforms/websites that contain video, have 64% more views compared to others that do not have video. About 65% of potential customers, visit the sales site after viewing a video and 70% of marketers say that video convinces the customer, better than any other medium (https://tourismmarketing.agency).

In tourism and the development of tourism activities, YouTube is the most used website for watching travel videos. About 79% of people looking for travel options use Google's online platform, with about 66% of potential travelers turning to video when researching tourist destinations. Also, about 65% of travelers turn to video when choosing a destination to visit. 54% view video when they are choosing accommodation and 63% of travelers watch video when looking for activities to do in their chosen destinations (Google2014).

According to Cisco, the forecast for the current year 2021 is that 85% of internet traffic will be driven by video consumption (Cisco, 2018). Given the data presented, the multimedia content for the promotion of nautical tourist destinations involves leveraging multimedia content on the platforms presented and enhancing their use/sharing by users and tourists. The creation of audiovisual content is currently based on new concepts, developed with new technologies such as drones or action cameras, which allow content to be properly prepared to convey the experience, emotion, and feelings of the destination to be shown.

In the specific case of the Nautical Resorts and wakeboarding, there is also the promotion of the locations, through Broadcast (television or Live Streaming transmission of major sporting events, such as stages of the wakeboarding world championship and with promotional activities such as those carried out in the city of Tomar on the river Nabão (Portugal). Thus, the promotion of nautical tourism destinations associated with major organizations and brands boosts the destination through the practice of the sport and develops the territory where nautical tourism is sought after for the practice of tourist and cultural activities. The use of multimedia platforms based on web and mobile platforms enables the dissemination of content and the promotion of the territory(ies) where nautical activities are carried out, thereby differentiating nautical tourism destinations.

5 Conclusions

This article has shown that in the Médio Tejo region, natural amenities such as rivers, reservoirs, and lakes, as well as the nautical activities that are promoted, especially nautical tourism, boost the local tourism offer. Furthermore, nautical tourism and all the tourist and cultural offerings related to this booming practice, broaden the possibilities for tourists to stay, improve the image of the destination and diversify the possibilities for increasing the positive impacts of the activity, especially on the economy.

Beyond the promotion of a tourist typology that provokes well-being with the practice of water sports, nautical tourism in the Médio Tejo represents the promotion of sustainability and responsible management of the resource.

Among the various ways of promoting tourist destinations, those that use marine and river water resources as territorial environmental assets must have as a premise the sustainable use of these heritage assets. In this work it is observed that the studied territory presents this concern and presented a nautical tourism proposal that not only values the water, heritage, and environmental resources, but that consciously, provides positive impacts for the population and for the resource itself about its enhancement and conservation.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has elected among the 17 goals a special focus on water. Goals 6 and 14 have, in addition to their scope, the possibility of promoting awareness and consciousness-raising for the protection of river water resources. This way, water presents itself, besides being an important development indicator, a tourist resource that should be planned in a conscious and responsible way. Thus, among the many types that tourism and its practice currently present, nautical tourism proves to be a great ally in achieving these objectives.

The data presented in this paper, show that the performance of the Intermunicipal Community of Médio Tejo (CIMT) by providing the infrastructure, with the creation of cable parks and in the near future the Castelo do Bode Nautical Station, in the Albufeira do Castelo do Bode, is of paramount importance to ensure that a resource so essential to human life is managed, used and is able to provide welfare not only for tourists, but for the entire community, with responsibility and environmental concern.

Furthermore, the existing Water Stations in the Centre region, the wakeboarding modality and all its online broadcasting is an important differentiator of the destination's offer and a great tool in the insertion of the destination in the new digital trends.

Nautical tourism in the Médio Tejo region is thus making a major contribution to the promotion of sustainable, responsible, and creative tourism. The multiplier effect of nautical tourism found at Albufeira do Bode can be a reference in the practice of sport, in the sustainable management of the river water resource and in the management of the tourist destination.

Consequently, research that understands the multiplier effect on the economy, the protection of the environment, the awareness of the use of the water resource through the practice of water sports and the importance of this activity for the region becomes necessary in future studies.

REFERENCES

Andereck, K., Valentine, K., Knopf, R., & Vogt, C. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (4), 1056–1076.

Andriotis, K. (2005). Community group’s perceptions of and preferences for tourism development: Evidence from Crete. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 29 (1), 67-90.

Baloglu, S., & Brinberg, D. (2001). Affective images of tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 35 (4), 11-15.

Beyer, B. D., Anda, M., Elber, B., Revell, G. & Spring, F., (2005). Best Practice Model for Low-impact Nature-based Sustainable Tourism Facilities in Remote Areas. Australia: CRC for Sustainable Tourism.

Buck, E. (1993). Paradise Remade: The Politics of Culture and History in Hawai'i. Temple University Press. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14bt4jw

Cisco (Hardware de Redes) - Retrieved from https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.html)

Comscore (Ross-Platform Measuremen) - Retrieved from https://www.comscore.com/.

Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (2008). Tourism: Principles and Practice (4th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Crouch, J. Mazanec, M. Oppermann, & M. Sakai (2002). Consumer Psychology of Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. London: CAB International, Volume 14, Issue 2, 193-211.

Davidson, R., & Maitland, R. (1997). Tourism Destinations. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Direção Geral de Política do Mar. (s.d.) - https://www.dgpm.mm.gov.pt/

Edensor, T. (1998). Tourists at the Taj: Performance and meaning at a symbolic site. London: Routledge.

Leisen, B. (2001). Image segmentation: the case of a tourism destination. Journal of Services Marketing, 15 (1), 49-66.

Eusébio, C., & Carneiro, M. J. (2012). Impactes sócio-culturais do turismo em destinos urbanos. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 30 (1), 65–75.

Figueiredo, P., & Almeida, P. (2017). Turismo Náutico. Capítulo 16. In F. Silva, & J. Umbelino, Planeamento e Desenvolvimento Turístico. Lidel.

Framke, W. (2002). The destination as a concept: A discussion of the business-related perspective versus the socio-cultural approach in tourism theory. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 2 (2), 92-108.

Freseach - Retrieved from https://go.forrester.com/.

Gössling, S., (2002). Ecological footprint analysis as a tool to assess tourism sustainability. Ecological Economics, 43(2-3), 199-211.

Graci, S. & Kuehnel, J., (2021). How to increase your bottom line by going green, Green Hotel White Paper, Green Hotels and Responsible Tourism Initiative.

Hall, C. M. (2004). Planejamento Turístico: políticas, processos e relacionamentos (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Editora Contexto.

Johnson, H., Middleton, F., Mace, D., Stancliffe, A., Stone, P., Epis, L. & Thomson, A., (2012). Water Equity in Tourism – A human right, a global responsibility: Tourism Concern Research Report, Tourism Concern Action for Ethical Tourism.

Jordão, A. C. D. A. (2019). Os impactos do desenvolvimento turístico: uma análise participativa dos limites de mudança aceitável no centro histórico do Porto (Doctoral Dissertation, Universidade de Aveiro).

Kaplan, A. & Haenlain, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53, (1), 59-68.

Lage, B. H., & Milone, P. C. (2001). Economia do Turismo. São Paulo: Atlas.

Lee, G., & Lee, C. (2009). Cross-cultural comparison of the image of Guam perceived by Korean and Japonese leisure travelers: Importance-performance analysis. Tourism Management, Article in Press.

Leiper, N. (1995). Tourism Management. Melbourne: RMIT Press.

Lopes, E. R. & Simões, J. T. (2019). Economia circular aplicada ao turismo: perceção dos estudantes do ensino superior. Capítulo de Livro. Estevão, C; & Costa. C. (Eds.). Turismo – Estratégia, Competitividade e Desenvolvimento Regional: uma visão estratégica no setor do turismo. Novas Edições Académicas, 207-223.

Lopes, E. R. & Simões, J. T & Nunes, M. R. (2020). Turismo Cultural e Recursos Patrimoniais: evolução dos visitantes de um município. Pp. 11-42. Capítulo de e-Livro. Figueira, M; & Cortes, M. (Eds.). Turismo Patrimonial: o passado como experiência. Pelotas. 271.

Marins, S. R., Mayer, V. F., & Fratucci, A. C. (2015). Impactos percibidos del turismo. Un estudio comparativo con residentes y trabajadores del sector en Rio de Janeiro-Brasil. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo, 24(1), 115-134.

Martins, C. I. M. (2012). Turismo rural e desenvolvimento sustentável: o papel da arquitectura vernacular (Doctoral Dissertation, Universidade da Beira Interior).

Miles, J. (2014). Instagram Power. Publisher: New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Orams, M. (1999). Marine Tourism: Development, Impacts and Management. Tourism, Hospitality and Events. 1st Edition. London: Routledge. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Osland, G. & Mackoy, R., (2004). Ecolodge Performance Goals and Evaluations. Journal of Ecotourism, 3(2), 109-128.

Portugal, T. d. (2017). Estratégia Turismo 2027. Retrieved from https://estrategia.turismodeportugal.pt/sites/default/files/Estrategia_Turismo_Portugal_ET27.pdf

Portugal, T. C. d. (2021). A barragem de Castelo do Bode e o legado dos Templários. Retrieved from https://turismodocentro.pt/artigo/a-barragem-de-castelo-de-bode-e-o-legado-dos-templarios/

Santana, A. (2009). Antropologia do Turismo. São Paulo: Aleph.

Silveira, L. (2016). Turismo de Iates: Estratégia de Desenvolvimento para a Figueira da Foz. Tese de Doutoramento, Universidade de Coimbra.

Stamboulis, Y., & Skayannis, P. (2003). Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism. Tourism Management, 24 (1), 35-43.

Tejo, C. I. d. M. (2021). Estação Náutica de Castelo do Bode. Retrieved from https://mediotejo.pt/index.php/areas-de-intervencao/turismo/estacao-nautica-de-castelo-de-bode#conceito

Tourism Marketing. Retrieved from https://tourismmarketing.agency/travel-industry-blog/why-video-so-important-tourism-marketing-and-how-make-it-successful.

Um, S., & Crompton, J. (1990). Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 17 (3), 432-448.

Urry, J. (1995). Consuming places. London: Routledge.

Google - Retrieved from https://storage.googleapis.com/think/docs/2014-travelers-road-to-decision_research_studies.pdf