GENDER ISSUES AND SUCCESS FACTORS FOR FEMALE FOOD AND BEVERAGE MANAGERS IN GREEK LUXURY HOSPITALITY

Evangelia Marinakou1, & Stergiani Karypi2

1Department of People and Organizations, Bournemouth University, Talbot campus, Poole, BH12 5BB, UK, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

2Department of People and Organizations, Bournemouth University, Talbot campus, Poole, BH12 5BB, UK, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to provide a perspective of gender issues and success factors of female food and beverage managers in luxury hotels. Gender discrimination is prevalent in this male-dominated department hindering women from pursuing a career in this sector. Although, there is some evidence of progress in terms of reducing the gender gap and gender pay gap in managerial roles, female managers in hospitality still suffer financially. Still numerical representation is not mirrored in the roles that women play in the technical or managerial leadership of the sector. The employment ghettos still exist implying gender diversity and occupational segregation is prevalent in hospitality management with less opportunities available for female managers. In order to study the impact of gender, age in career progression and their impact on the glass ceiling phenomenon a qualitative research with 12 semi-structured interviews with female food and beverage managers in Greece was done. Gender issues were identified by all participants, although they claimed that the glass ceiling is not thoroughly evident in the workplace. Some faced age discrimination and others were troubled by the working conditions and expectations. Stereotypes still persist in Greece, as well as the pay gap. Female leadership style and management was proposed to be effective in luxury hotels as women are multitasking, supportive, demonstrate empathy and sympathy and bring good results. This study proposes that the HR departments in luxury hotels in Greece are non-effective and they do not pay attention to diversity. Female human capital should be appreciated and developed so that the Greek luxury product can face competition.

Keywords: Gender, Food & Beverage, Women managers, Glass ceiling

1INTRODUCTION

Gender gaps in labor force participation remain wide with underrepresentation of women in traditionally male-dominated sectors (ILO, 2018). The slow rate of progress suggests it will take another hundred years to achieve gender equality (Global Gender Gap Report, 2020). The recent pandemic of Covid-19 has hit hospitality further exacerbating inequalities. “Economic slowdowns not only disproportionately affect women, but also trigger gender equality topics to slip down governmental and corporate agendas” (Mahajan et al., 2020). Certain departments of the hotels are filled by men while in other departments mostly women are employed implying gender diversity in the hospitality industry is inadequate (Pinar et al., 2011). The hospitality and tourism industry faces shortage of trained staff, with labor-intensive, fragmented hotels. Still the hotel industry struggles to retain staff and more specifically talented female managers who aspire for careers in the industry (Marinakou, 2019). Mooney & Ryan (2009) suggested that the pervasiveness of gender-role stereotyping and the availability of jobs would make employment in the industry advantageous for talented women. Structures and the glass ceiling still prevent women from climbing the career ladder and “patterns of gender inequality persist in leadership positions” (Mooney & Ryan, 2009, p.196). Although there have been many positive steps and literature shows progression of women in managerial positions in the hospitality industry, supported by relative inclusion and diversity policies in place in many organizations, opportunities for female managers are still less than those for their male counterparts with similar qualifications and experience. Moreover, García-Pozo et al. (2012) proposed that the salary of men is fairly high compared to women even if they hold the same role in a company. When it comes to the Greek reality, Petraki-Kottis & Ventoura-Neokosmidi (2011) identified that women in Greece get only 65% - 80% of what their male colleagues gain.

Representation of women in managerial positions in the food and beverage (F&B) department is very low (Berry, 2020). For example, in the US 19% are women, while 77.5% are men. Interestingly, younger employees in the sector have observed gender bias in the workplace, and they have raised the need for diversity and inclusion. “ While women make up 49 percent of employees at the entry level, representation drops steeply at higher levels along the pipeline. At the top, women represent only 23 percent of the food industry’s C-suite executives” (Krivkovich & Nadeau, 2017, p.3). Still, 20% fewer women than men reach their first promotion to manager although there has been a push for more flexible work in the sector (Krivkovich & Nadeau, 2017, p. 8).

With a brief look at the current literature many countries around the world have already identified the need of change in the area of female management as there are many benefits for the organizations. Countries have proceeded in making plans for the inclusion of women in the senior management positions and utilizing the best of the women’s abilities. F&B operators should consider the social construction of gender that may support or restrict professional career and success. The gender roles in family life and in the workplace, particularly the role of women that still have in a family and a household has big consequences in a career in the industry. The aim of this paper is to explore the visible and invisible barriers that women face in managing the Food and Beverage (F&B) department as well as at identifying the success factors of those who managed to get to the top. The objectives of this study were to:

- Explore the experiences of F&B female managers in terms of the barriers they face at work;

- Identify the success factors of having a career in F&B management;

- Propose ways and strategies for female managers progression in F&B management.

2literature review

2.1Women in hotel management

According to the International Labor Organization (2018), gender gaps in labor force participation remain wide. Gender diversity has been a major issue over the years. There is progress when it comes to closing the gender gap in managerial roles in the hospitality industry as studies show that the hospitality industry consists of nearly 50% of female managers and the percentage of women being trained to become managers is over 75% nowadays (Berry, 2020). Women are more likely to suffer financially because women's professions pay less than men's professions. Gender differences in professional choice contribute to low wages for women, even if we account for differences in skills and credentials related to the work of men and women (Powell, 2018). The human capital theory highlights the contribution of education to increasing productivity in the workplace, as education equips employees with skills and qualifications valued by employers. Pay is attributed to the human capital (education, training and experience) each employee has. Women used to acquire less human capital due to domestic responsibilities limiting their opportunities for a career. Although, nowadays women are found to study hospitality management and have adequate experience, they still experience salary gaps.

Women are horizontally and vertically segregated into particular jobs in hospitality. They usually carry out lower status work and are horizontally segregated into particular areas of operation (Ng & Pine, 2003) or they are vertically segregated into jobs that are considered low status (Powell, 2018). The ‘pink ghetto’ is found in many hospitality organizations including those in Greece (Marinakou & Giousmpasoglou, 2019). Practice in the hospitality industry continues to stereotype the roles available for women, with the addition of sexual harassment, which is prevalent for female employees (Berry, 2020).

Inequality exists in hospitality management and women are excluded from managerial positions due to the glass ceiling phenomenon, the working conditions and stereotypes. Inequality refers to the systematic differences among colleagues in their power and control of organizational goals, resources, workplace decisions, opportunities for promotions, pay, and respect (Acker, 2006). Academic literature has shifted the focus of research into women in general management, keeping in mind their opinions and aspirations to develop their personal careers in the F&B department. The experience of individual employees in the hotel industry remains very much to be understood and this paper seeks to fill a knowledge gap in the perception of female F&B managers in luxury hotels.

2.2The glass ceiling and working conditions

The glass ceiling phenomenon implies an invisible structural barrier in institutional life for groups with differentiated by diversity categories (i.e. age, gender) (Acker, 2006). A lot of research has been published on the phenomenon of the glass ceiling suggesting that the ‘glass ceiling’ exists; many even propose that even if women are well positioned in their early careers there is no guarantee that they can maintain equality in the workplace (Santero-Sanchez et al., 2015). A lot of studies discuss the problems women encounter in their careers but very few refer to the ways women overcome these barriers (Remington & Kitterlin-Lynch 2018), which is the purpose of this paper.

Fernandez & Rubineau (2019) propose that the glass ceiling is linked to the old boys’ network. It refers to informal social networks of men with similar demographics, who are strong professionals, established and support and sponsor each other (Powell, 2018). An outsider is a member of the opposite sex with limited access to social capital (Beaman et al., 2018). In contrast to men, women provide support and professional help to each other without forming informal networks (Durbin, 2011). Evidently, the more connected the members of the old boys network are, the more social capital is accumulated, the harder it is for a feminization process to happen or for women to be included. Social capital refers to a “person’s standing or reputation in an organization depending on the social network that they have built up with mentors, peers and superiors, and its complex interaction of favors owed and received” (Mooney & Sirven, 2008). Domestic duties occupy a lot of time, hence female managers do not focus on networking, training and other activities valuable for career progression (Marinakou, 2014). Women usually are found to have more responsibilities than men even at sharing household arrangements (Budworth et al., 2008). Tharenou (2005) mentioned that marriage, maternity leave and the traditional household division of chores hinder women to achieve more relevant roles in enterprises.

Social factors impact on women’s career progression (Marinakou, 2014). Hospitality is prone to labor mobility, making relocations for promotion a detrimental factor on female managers’ personal life (Powell, 2018). Altman et al. (2005) suggested that men usually get promoted by remaining at their organization whereas women have to move to other. Empirical research highlights factors such as long and irregular working hours, old boys’ network, hiring practices, geographical mobility and lack of role models to hinder women’s career progression (Marinakou, 2014). Many women choose to leave the industry when they have families and children (Baum, 2015), demonstrating issues with work-life balance. Studies in the UK propose that gender employment discrimination is not that evident, with very small wage gaps and policies including family taxation, childcare benefits, parental leaves, flexible working patterns and anti-discrimination laws (Livanos et al., 2009). Differences between Greece and the UK are also observed based on the economic structure, institutional characteristics (i.e. existing diversity policies), personal attributes of female managers (i.e. education, region, age, marital status) (Livanos et al., 2009). Lack of role models to support women is also evident in hospitality management, and more in the F&B department.

Hotel management practices reflect such organizational cultures that reproduce corporate patriarchy; gender stereotypes of women are deeply rooted in modern Greece's patriarchal society (Mihail, 2006; Marinakou, 2008). Thomas (2005) suggested that in patriarchal society organizations show "hegemonic masculinity" referring to practices that legitimize men's power over women (Marinakou 2014). There is the belief that managerial positions require aggressiveness, assertiveness, leadership styles and traits that women are lacking (Powell, 2018). Others claim that women’s leadership styles are similar to men (Marinakou, 2014). There are different perceptions of men and women as managers. Women are thought to be more emotional and democratic, and men more adequate to be managers as they focus more on financial results (Powell, 2018). As stated by Eagly & Karau (2002), the incongruity between expectations about women (i.e., the female gender role) and expectations about leaders (i.e., leader roles) underlie prejudice against female leaders. Similarly, Mihail (2006) proposed that women in corporate Greece face attitudinal barriers. Gender stereotyping persist in Greek culture supported by the underrepresentation of women in managerial positions (Petraki-Kottis & Ventoura-Neokosmidi 2011). Gender stereotypes, cultural barriers, dual role, visibility factor, gender segregation are also factors preventing women from participating in management (Marinakou, 2014; Baum, 2015). Gender roles in society mitigate chances for women to progress their career (Baum, 2015), limiting the female talent.

2.3Facilitating factors for career progression

There are strong arguments on whether the barriers are self-imposed or caused by external factors. Nevertheless, studies propose some ways that facilitate career progression for female managers. Such strategies include participative leadership (Remington & Kitterlin-Lynch, 2018) and transformational leadership (Marinakou, 2014) styles to be adopted by female managers. These styles are linked to improved performance, high levels of organizational commitment, and employee empowerment. Flexibility in the workplace is important quality for success and studies propose that female leaders are more flexible than their male counterparts (Caliper, 2015). Proactivity is also another key element as women should take a proactive approach to manage their careers with activities such as networking, developing and maintain relationships that support advancement or further professional training (Remington & Kitterlin-Lynch, 2018). Organizational policies and practices should also support training.

3methodology

This study used the qualitative approach that supports inductive purposes. In order to understand the phenomenon of women’s underrepresentation in F&B management and make sense in terms of women’s meaning (Denzin & Lincoln, 2013) qualitative research was found to be appropriate. Qualitative interviews were used, which led to in-depth data gathered in order to get a deeper understanding about the circumstances of each individual who was interviewed. A list of 13 questions, based on the literature review, were used to lead the discussion and to encourage female managers to express their perception of their career success. Convenience sampling was used as very few women are found in such positions in the Greek hospitality sector. 12 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with women who worked in the F&B department of Greek hospitality establishments, having various ages and experience in order to maximize the quantity and quality of data gathered. The participants were working full time, were highly educated with degrees in hospitality and tourism management as well as experience in their field. The invitation email informed participants about their freedom to participate and their anonymity; they were also sent the list of questions to have an idea of our discussion. All interviews were conducted in Greek, and audio recorded to allow proper transcription and translation into English which was performed by the two authors. Thematic analysis was then performed to identify the key themes, to make sense of collective and shared meanings and experience of participants in the study (Braun & Clarke, 2012).

4key findings AND DISCUSSION

4.1Participants’ background and current situation in Greece in F&B management

The female F&B managers in this study appear to be hopeful for the future confirming Baum (2015) and Powell (2018) who support that there have been attempts to decrease the gender inequality in hospitality. But we can also observe that the participation of women is low and one of the explanations is based on the belief that managerial positions require aggressiveness, leadership styles and personality traits that women are lacking.

One of the most interesting facts about this research is the variety of distinct characteristics of each interviewee. Starting from age, it was observed that older women tend to get higher positions. The youngest of the interviewees emphasised how they got the job, referred to being bold and believing in themselves, and while they had no experience they took the risk, while some of the others that were older experienced segregation because of their age. P7 was an F&B manager at the age of 26 in Greece and she faced the mentality of the Greek working culture of being too young to be in the role. All were educated with undergraduate and/or postgraduate studies and a lot of experience. Two were married with children.

Hard work, long working hours and the nature of work prevent many young women to avoid a career in this department. Men remain the majority in this department and companies prefer male employees for such positions as “they find men more suitable for the job” (P14).

4.2Glass Ceiling

The participants’ opinions on the glass ceiling differ from each other and none of the women seemed to agree fully with Santero-Sanchez et al. (2015) about the glass ceiling being thoroughly evident in the workplace. There were those women that have not encountered obstacles, whilst others faced age discrimination. The views of each participant are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Participants’ opinions on the glass ceiling

|

P1, P6, P12 |

P2, P9 |

P7, P8, P10 |

P4, P11 |

P6, P12 |

P3, P5 |

|

Glass ceiling encountered, appearance matters |

Faced a couple of times |

Discrimination encountered, mainly due to age |

Haven’t faced any barriers |

Encountered due to the culture in Greece |

Being optimistic (hard work required) |

Interestingly P6 said she encountered obstacles in her career and “especially in Greece, where if you don’t have the right connections or being liked by your director, you are not going to get promoted, whatsoever”. P1 said “most of the times when a woman gets a promotion it is because she looks nice!” providing evidence of bias in hiring women in a masculine culture (Mooney & Ryan, 2009). P10 appeared to be in the same position. Because she is a woman she has been sexually harassed and in addition, her male colleagues took all the promotions even though she was more qualified. Her director at the time told her face to face that she was not entitled to promotion because she had a child and she was a mother. P6 claimed that in her sector of employment there are no right human resource practices implemented. For a woman to be a manager, long working hours prevent her from being married or being a mother and “in this industry there are some measures being taken, but only as to protect women from not being fired, when it comes to family matters. Schedule, maternity leave, parental leave would be some of the things that could be added

to make them more effective”.

4.3Female Leadership

All of the participants noticed that there are differences in the way males and females lead a team, but female leadership was found to be effective, as they were found to be multitaskers and more capable of handling difficult situations, with strong emotional intelligence, more organized and more compassionate towards coworkers or guests needs confirming other studies (Marinakou, 2014). It is exceptionally difficult for women to achieve the recognition that they deserve for their abilities and achievements and are required to show extra competence (Marinakou, 2014; Baum, 2015; Powell, 2018) so as a result, female leaders tend to work harder and they are looking for leadership styles that do not unnecessarily provoke resistance to their authority by challenging standards that dictate women's egalitarianism and others’ support. P2 said “it’s all about personality and skills, not gender”, P4 agreed and added that “leadership style between males and females in her view is completely different. Females are more effective as leaders because they are characterized by strong emotional intelligence. They are more caring about their staff, which is the key to build respect and inspire your team members. Also, they try to create a balance between personal life and work, not only for them but also for their staff, which is highly appreciated”. Compassionate and more organized are some of the traits given by P6, highlighting that men tend to overestimate their abilities. “Women are more insightful”, says P7 and more emotionally intelligent. They can be strong without being intimidating, but they have to prove that they can work as hard as a man but show empathy as well.

4.4Stereotyping and Social Role

Gender stereotypes of women are deeply rooted in modern Greece's patriarchal society (Mihail, 2006; Marinakou, 2008) and Thomas (2005) declares that in patriarchal society organizations show ‘hegemonic masculinity’ referring to practices that legitimize men's power over women (Marinakou, 2014). All of the participants supported that the stereotypes in Greece still persist, agreeing completely with the existing literature (Petraki-Kottis & Ventoura-Neokosmidi, 2012). P1 supports that she faced stereotypes all the time and she mentioned that 20 years ago, the manager of a big hotel chain in Athens told her that the only problem was that she was a woman. The study also proved that the pay gap is in place in Greece when it comes to female managers and that in general hospitality is a very low paid sector. Culture was also identified by participants as hindering women’s careers in Greece. P7 believed that the obstacles were not encountered because she was a woman but because she was in Greece. “I don’t allow people to think of me less because I am a woman and because I am a quite strong personality people don’t do. But in Greece, because I was an F&B Manager by the age of 26, with an MBA degree, I did have to face the mentality of too young to be in a role”. P6 added the need for equal treatment for every employee, according to their abilities and knowledge, regardless of gender, age etc.

4.5 Reasons for success

All participants talked about hard work, which is a requirement of work in the F&B department. They also said that they had to be both mentally and physically capable in order to succeed and be able to put extra effort. Their love for their profession was the starting point of pursuing a career in F&B management. Ambition, believing in yourself and diplomacy were other traits for success. P3 said “In an industry full of men, you have to be really careful of your actions

around the working environment”. P2 mentioned “you have to isolate personal life from work”, suggesting to have a good work-life balance. They all proposed that organizations and people should give others chances to grow and use leadership as P11 said “if you don’t help others develop, you never grow yourself”.

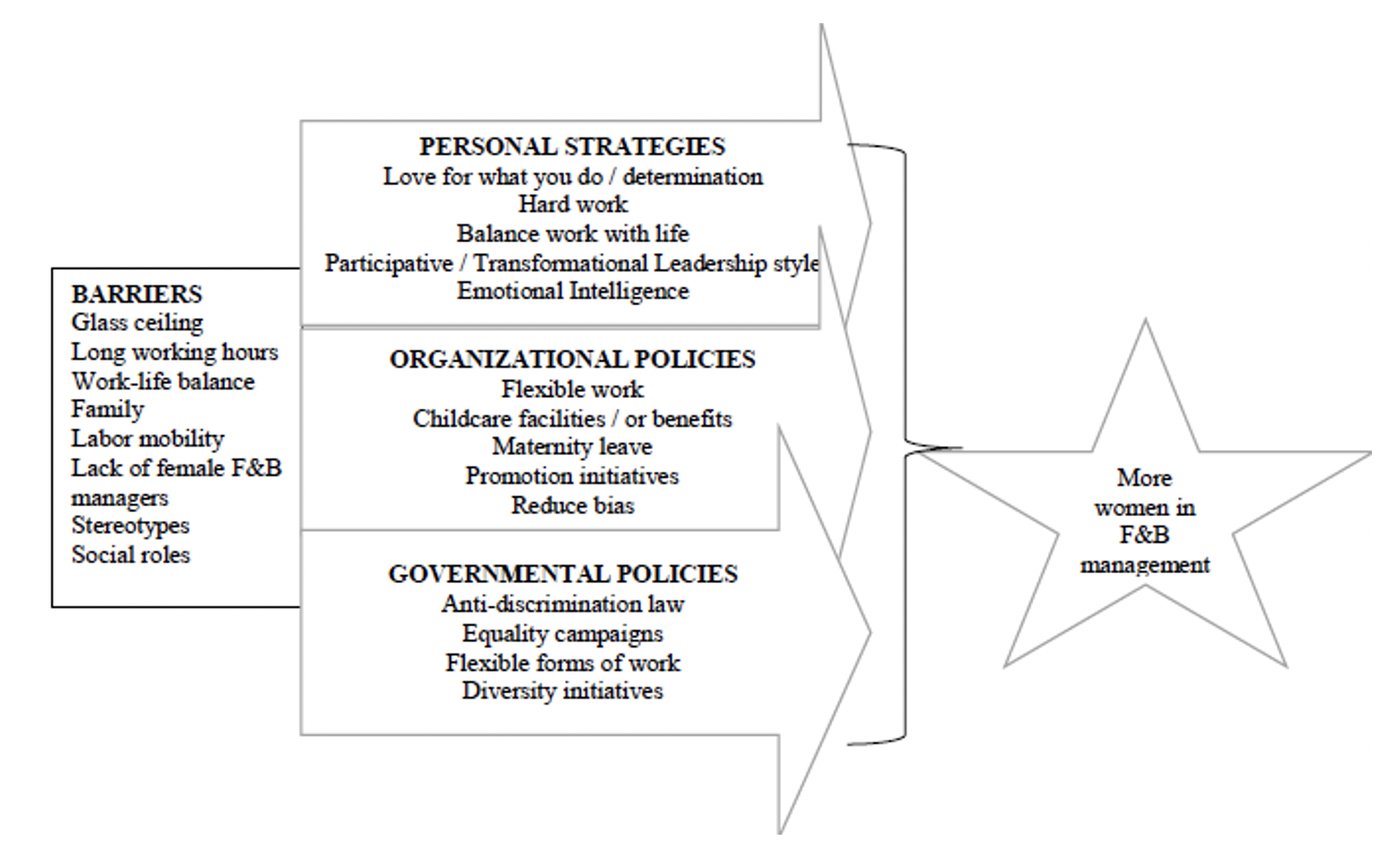

Graph 1 summarizes the barriers that women face in F&B management and the proposed strategies for success in the sector.

5 Conclusions

5.1Conclusions

There is extensive investigation in the area of gender disparity, but most studies do not address the reasons why these barriers occur and how female employees overcome these barriers. This study sought to explore the reasons for female F&B managers underrepresentation in hotels. The main aim was to identify the factors for success of those who already occupy such positions. This paper proposes that in Greece, the HR department is either non effective, non-existent or conducting basic HR operations, without giving much detail to what the employees really need. Although legislation for equal opportunities has been established in Greece, hotels have not yet realized the importance of female human capital and talent. Competition among hotels in Greece has grown especially since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, but still women are underrepresented in food and beverage management (Belias et al., 2017). Women are still facing barriers in pursuing a career in this department, which is found to be male-dominated. Interestingly, participants are hopeful for the future, and expressed the view that gender inequality will decrease further. Key barriers were long working hours, issues with work-life balance, age discrimination, gender roles, stereotypes and the lack of female managers to become mentors and support young professionals. Success was based on factors such as hard work, and work-life balance. Although the literature shows that there is prejudice against female leaders effectiveness (Mihail, 2006), participants in this study support that female leadership is more effective in the context of hospitality sector confirming other studies on women’s position in hospitality management (Marinakou, 2008). Stereotypes still persist in Greek hospitality (Petraki-Kottis & Ventoura-Neokosmidi, 2011), the wage gap is still large, however this study proposes that female F&B managers rely on education, experience, training, professional development, determination to succeed and their leadership style to promote their effectiveness in managing people and their departments.

5.2Practical Implications

This study provides directions for managing female managers in hotels and for promoting policies that will support women’s development and existence in F&B management. Hotels should be ready to address any discrimination that occurs in the workplace with relevant anti-discrimination policies, diversity management and training. The legal framework that supports equality at work should be part of human resources management. For example, adequate policies should be in place that provide support for balancing family with work, childcare could be provided or a relevant benefit could be provided. Such policies are not always followed creating frustration to employees. Evidence from the UK shows that job satisfaction is high when equal opportunities policies are in place in luxury hotels (Marinakou & Giousmpasoglou, 2019).

Hospitality organizations should reduce negative beliefs and attitudes towards female managers and provide them with the environment and circumstances to use their skills and talent in F&B management. They should train employees on gender bias and discrimination. Getting more female managers in male-dominated departments and/or putting more women in line for promotion should be a priority of human resources strategy. Furthermore, fair recruitment criteria, equal opportunities for promotion should be the norm rather than the exception. Non-traditional work hours, flexible job schedules, job sharing could be practices to be explored by F&B managers.

Mentoring is important however the lack of women managers in F&B reduce the opportunities for practicing this. Such programs should be planned, directed by senior management to accomplish long-term goals. High potential female employees could be mentored to support them advance in hierarchy.

5.3Limitations and future research

This study has some limitations. The main limitation is the small sample size, although not many women were found to lead F&B departments. Future studies should attempt to find a larger sample and include women F&B managers from other countries as well. A comparison could be made with the UK hospitality industry where more practices on equal opportunities are found.

Future studies can also include quantitative analysis and provide measurement of the phenomenon of the glass ceiling and gender discrimination in F&B management. The present paper provided a more holistic approach to the issue, however studies may investigate any differences in terms of hotel type and capacity, and/or in terms of regions.

REFERENCES

Acker, J. (2006), ‘Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations’, Gender & society, 20 (4), pp.441-464.

Altman, Y., Simpson, R., Baruch, Y. & Burke, R. (2005), ‘Reframing the ‘glass ceiling’ debate’, in Burke, R. (Ed.), Supporting Women’s Career Advancement, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Baum, T. (2015), White paper on Women in Tourism and Hospitality: Unlocking the talent pool. HIP Coalition. Hong Kong.

Beaman, L., Keleher, N. & Magruder, J. (2018), ‘Do job networks disadvantage women? Evidence from a recruitment experiment in Malawi’, Journal of Labor Economics, 36(1), pp.121-157.

Belias, D., Trivellas, P., Koustelios, A., Serdaris, P., Varsanis, K. & Grigoriou, I. (2017), ‘Human resource management, strategic leadership development and the Greek tourism sector', Tourism, culture and heritage in a smart economy: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, pp. 189-205. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-47732-9_14

Berry, D. (2020), Women underrepresented at senior levels of food and beverage manufacturers, Available at: https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/15346-women-underrepresented-at-senior-levels-of-food-and-beverage-manufacturers

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006), ‘Using thematic analysis in psychology’, Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), pp.77-101.

Budworth, M., Enns, R. & Rowbotham, K. (2008), ‘Shared identity and strategic choice in dual career couples’, Gender in Management: An International Journal, 23(2), pp. 103-19.

Caliper. (2015), Qualities that distinguish women leaders. Princeton, NJ: Caliper Headquarters.

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011), The Sage handbook of qualitative research. New York: Sage.

Eagly, A. H. & Karau, S. J. (2002), ‘Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders’, Psychological review, 109 (3), p.573.

Fernandez, R. M. & Rubineau, B. (2019), ‘Network Recruitment and the Glass Ceiling: Evidence from Two Firms. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 5 (3), pp.88-102.

García-Pozo, A., Campos-Soria, J. A., Sánchez-Ollero, J. L. & Marchante-Lara, M. (2012), ‘The regional wage gap in the Spanish hospitality sector based on a gender perspective’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), pp. 266-275.

Jamhawi, M., Al-Shorman, A., Hajahjah, Z., Okour, Y. & Al Khalidi, M. (2015), ‘Gender equality in tourism industry: A case study from Madaba, Jordan’, Journal of Global Research in Education and Social Science, 4(4), pp.225-234.

ILO (2018), Global Wage Report 2018/19. What lies behind gender pay gaps. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Krivkovich, A. & Nadeau, M. (2017), ‘Women in the food industry’, McKinsey report, Available at: www.mckinsey.com.

Livanos, I., Yalkin, C. & Nunez, I. (2009), ‘Gender employment discrimination: Greece and the United Kingdom’, International Journal of Manpower, 30(8), pp.815-834.

Mahajan, D., White, O., Madgaykar, A. & Krishnan, M. (2020), ‘Don’t let the pandemic set back gender equality’, Harvard Business Review, 16 September.

Marinakou, L. (2008), ‘Do men and women lead differently in hospitality?, Conference Proceedings, “1st International Conference on Tourism and Hospitality Management”, T.R.I. - Tourism Research Institute (ΔΡ.Α.Τ.Τ.Ε.), Athens, 13-15 June.

Marinakou, E. (2019), ‘Talent management and retention in events companies: Evidence from four countries’, Event Management, 23, pp.511-526.

Marinakou, E. & Giousmpasoglou, C. (2019), ‘Talent management and retention strategies in luxury hotels: Evidence from four countries’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , 31(10), pp.3855-3878.

Mihail, D. M. (2006), ‘Women in management: gender stereotypes and students' attitudes in Greece’, Women in Management Review, 21(8), pp.681-689.

Mooney, S.K. & Ryan, I. (2009), ‘A woman’s place in hotel management: upstairs or downstairs?’, Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(3), pp.195-210.

Ng, C.W. & Pine, R. (2003), ‘Women and men in hotel management in Hong Kong: Perceptions of gender and career development issues’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 2(1), pp.85-102.

Petraki-Kottis, A. & Ventoura-Neokosmidi, Z. (2011), Women in management in Greece. Women in Management Worldwide: Progress and Prospects. Farnham: Gower Publishing Limited.

Pinar, M., McCuddy, M. K., Birkan, I. & Kozak, M. (2011), ‘Gender diversity in the hospitality industry: an empirical study in Turkey’, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30 (1), pp.73-81.

Powell, G. N. (2018), Women and men in management. New York: Sage Publications.

Remington, J. & Kitterlin-Lynch, M. (2018), ‘Still pounding on the glass ceiling: A study of female leaders in hospitality, travel, and tourism management’, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 17(1), pp. 22-37.

Santero-Sanchez, R., Segovia-Pérez, M., Castro-Nuñez, B., Figueroa-Domecq, C. & Talón-Ballestero, P. (2015), ‘Gender differences in the hospitality industry: A job quality index’, Tourism Management, 51, pp. 234-246.

Tharenou, P. (2005), ‘Women’s advancement in management: what is known and future areas to Address’, in Burke, J. and Mattis, M. (Eds), Supporting Women’s Career Advancement, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 31-57.

Thomas, A. B. (2005), Controversies in management: Issues, debates, answers. New York: Routledge.

World Economic Forum (2020), Global Gender Gap Report 2020.